The CFT turns 100 on May 31, 2019. To kick off this anniversary year, California Teacher digs into the archives to present a commemorative issue about the rich history of our statewide federation of unions. The big events — legislation, elections, social trends — described here affected every member. But this capsule history cannot possibly relate the profound impact almost 100 years of activism had on thousands of individual education workers. Nor can these summaries relate the thousands of actions taken by individuals, each one for the greater good, each one completed so that all of us, brothers and sisters, might benefit. We look forward to another 100 years of fighting for our students and each other.

Roaring Twenties

The birth of a statewide federation of teachers

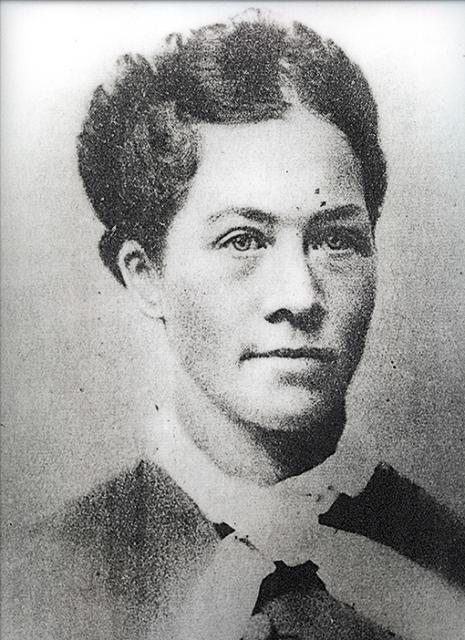

THE FIRST KNOWN union activist in California public education was Irish immigrant Kate Kennedy. Kennedy fought against sex discrimination in San Francisco when she became a principal and discovered male principals made more money than she did. She was not a member of an educators’ union, but belonged to the Knights of Labor, an organization for working people dedicated to the collective values of a “producers’ commonwealth.”

In 1874, Kennedy successfully lobbied legislators to pass a state law guaranteeing educators “equal pay for equal work.” This turned out to be a fleeting victory. To get around the law, school administrators simply kept elementary wages lower for the mostly-female teachers; they kept secondary school wages higher for the mostly male teachers.

Successful resolution of this problem would take nearly 100 years and a public education union movement that would peak with passage of the state Educational Employment Relations Act in 1975. A major marker in that movement was the formation of the California State Federation of Teachers in 1919, three years after the birth of the American Federation of Teachers.

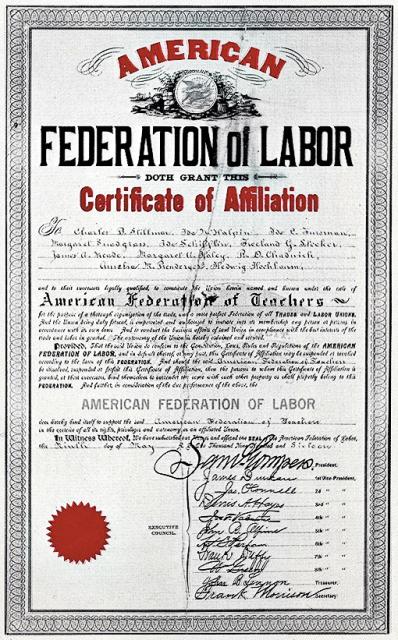

THE FLEDGLING AFT had chartered several local unions in Northern California. Just months after its own founding, the San Francisco Federation of Teachers, AFT Local 61, hosted seven other newly chartered AFT locals in discussions about creating a state federation of teachers’ unions.

On May 31, 1919, representatives of these eight small but determined organizations agreed to found a state federation for two stated purposes: to serve as an information clearinghouse for locals, and to give teachers a means to express their opinion on statewide education matters. At their second meeting in October, the locals formally established the California State Federation of Teachers. The group elected Sacramento High School teacher Samuel McLean its first president, and Olive Wilson, an elementary teacher from Vallejo, vice president.

Longtime San Francisco Federation president Paul Mohr, also statewide president in the late 1920s, recalled the founding in American Teacher, June 1927. He said that two objectives had been left out of public statements at the time: “to bind the young locals firmly together against attacks from enemies of the teacher-union movement” and “to build up a central fund for the defense of any teacher suffering unjust treatment at the hands of local school officials.”

There were plenty of those in the 1920s. California was especially hard-hit by the notorious post-World War I hunt for “subversives” led by U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. Teachers were taunted, publicly humiliated, and fired for expressing views mildly dissenting from those of ultra-patriotic groups.

Without a law enabling collective bargaining — an ultimate objective of the CSFT — the statewide Federation and its locals relied on legislative and political action, as well as legal defense, to advocate on behalf of its members and public education.

BEFORE THE AFT ARRIVED in California, the preeminent organization of educators in the state, as in the nation, was the National Education Association. Founded in 1856, the NEA was dominated by administrators, superintendents, and school board members, all of whom were men. Teaching was not accorded the respect of a profession and teacher voices were barely heard. But when the possibility of collective action or public demonstrations on behalf of teachers arose, such “impolite maneuvers” were promptly labeled “unprofessional.”

In the early part of the 20th century, teacher unions largely defined themselves in opposition to the NEA and instead identified with the labor movement, which was growing in strength and influence. Teachers saw the power of collective bargaining for carpenters and mechanics and other craft workers to achieve job protections and increased standards of living.

At its birth the new CSFT boasted nearly 800 members. Recruitment exceeded everyone’s expectations at first, and hopes were high for rapid expansion. From the outset the strength of the union was in Northern California, except for the chartering of Local 77 in Los Angeles, which no longer existed by the late 1920s. It wasn’t until the mid-1930s that locals began forming in Southern California.

Membership numbers fluctuated wildly in some locals from year to year due to recurring bouts of administration and civic pressure, and inconsistent resolve on the part of the teachers. Even worse, teachers willing to organize often faced the disappearance of entire locals shortly after their chartering. Of the 10 California locals that appeared in 1918–19, only Sacramento and San Francisco were still thriving by 1930. Several more had formed in the meantime, but their future was uncertain.

EVEN IN THESE DIFFICULT TIMES, the CSFT boasted important accomplishments. With Labor Council assistance, the San Francisco Federation gained reinstatement for two suspended teachers. The CSFT helped a number of teachers in legal suits, mostly for wrongful dismissal. In Santa Cruz, Albany and other cities, the state union assisted teachers in winning through the courts what it could not achieve through local strength. One major success occurred in Fresno, where several teachers had been dismissed for “incompetence.” The Federation undertook a libel action against the superintendent and won.

Labor support was instrumental in passing the 1921 state tenure law, one of the most progressive in the country at the time. The law provided for a public hearing and representation by counsel at dismissal after two years of probationary teaching. CSFT President McLean and San Francisco’s Mohr worked closely with the California Labor Federation to ensure passage. Unfortunately, the law was amended in 1927 to exclude teachers in smaller districts, and hostile forces continued to chip away at it throughout the next decade.

The first decade of the California State Federation of Teachers was challenging. The conservative political atmosphere of the “Roaring Twenties” took its toll, and deep-seated prejudices against women, unions, and teacher organizations combined to sap the energies of all but the most devoted CSFT adherents. Nonetheless, the new organization had established itself as a clear voice for teachers and forged strong bonds with labor, the bedrock of its social support. It had survived.

The Depression and War Years

Workers and their unions struggle to survive

In the 1930s, major forces threatened the existence of the California State Federation of Teachers. The Depression drastically affected teachers, as did recurring Red Scares. Internal stresses divided the labor movement as a whole, as well as the fledgling AFT, making the lot of teachers worse than when the AFT had formed in 1916.

Teachers faced the bleak prospects of wage reductions, school closings, larger classes, reduced services, and job cuts. The entire labor movement suffered during the national economic collapse of the Great Depression. More than a quarter of the population was unemployed, and membership in the American Federation of Labor dwindled to less than 10 percent of the workforce.

The craft-oriented AFL lacked the vision to organize the new mass production industries, and a split developed over its lack of militancy. Several unions, pushed by the United Mine Workers under John L. Lewis, broke away from the AFL in 1935 to form the Congress of Industrial Organizations — the CIO.

This in turn created a schism in the AFT, which considered leaving the relatively conservative AFL for the militant CIO. After protracted debates, the AFT decided to work for the unity of the two labor federations from within the AFL.

DESPITE ITS INTERNAL conflicts, the AFT made slow but steady progress throughout the 1930s. Meanwhile in California, stagnation ruled. Recurrent reports of the organization’s “rebirth” make it clear that the CSFT struggled for survival in the 30s and 40s.

In 1941, with union resources spread thin and male teachers facing World War II and the draft, the AFT revoked the charter of the 250-member California State Federation of Teachers for maintaining less than five local unions in good standing. But by 1944, nine AFT locals were founded in California, and CSFT’s charter was reinstated.

CSFT took a new direction under Ed Ross, a full-time classroom teacher from Local 771 in Alameda. FDR’s New Deal programs and a booming war industry had moved the economy forward. Ross developed an organizing plan, and, with the help of the California Labor Federation and the AFT, he worked to organize both ends of the state.

Acting on the resolve of Ed Ross, all AFL unions condemned loyalty oaths as a condition of employment for teachers. A long-promised newsletter, California Teacher, began reporting these successes in 1948, and has maintained regular publication since.

Ross was re-elected in 1949. Despite teacher reluctance to join the union during the Cold War, Ross helped form eight more locals, building membership to nearly 1,000 teachers.

The 1950s Red Scare

Defending constitutional rights and academic freedom

Each decade had its own Red Scare. In 1938, the new House Un-American Activities Committee turned its baleful eye on teachers’ union activities. The AFT and other organizations defended the constitutional rights of teachers, aided by the growing strength of the labor movement and FDR’s administration

The 1940s Red Scare diverted AFT and CSFT energies to defending against charges of communist domination. AFT faced an uncertain future. McCarthyism ended many teaching careers, and even lives: The first teacher called to testify before the HUAC committed suicide on Christmas Eve, 1948.

Moving into the 1950s, the CSFT battled to preserve civil liberties, opposing loyalty oaths and defending academic freedom. It also took on tenure and cases concerning working conditions.

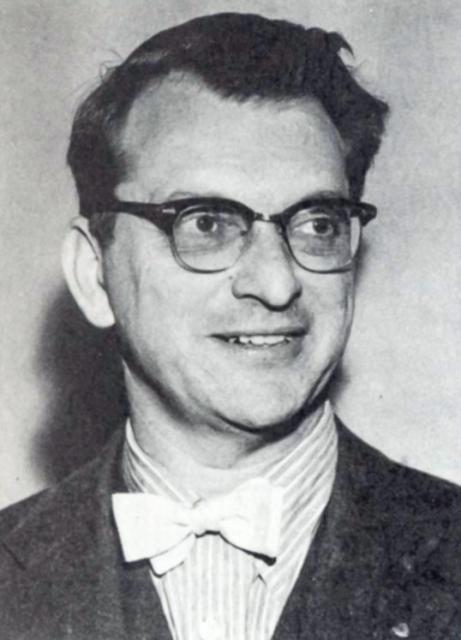

In 1951, the influential president of the Contra Costa County Federation of Teachers, Local 855, Ben Rust, led the CSFT and helped define what the CFT is today. Rust built the union into a stable statewide presence through regular meetings and publications, legislative proposals, slow but steady membership growth, and healthy relationships with other unions. CSFT hired its first full-time staffer and retained an attorney with legislative and legal duties.

CSFT carried bills in the California Legislature prohibiting discrimination in hiring, and proposing pay raises, duty-free lunch periods, and collective bargaining for teachers. When Rust stepped down after seven years, the CSFT had nearly tripled in size and there were 26 AFT locals in California.

Lou Eilerman, an art teacher from Long Beach, headed the CSFT next. Eilerman moved the union into an office, and began organizing university and community college locals. He would lead the CSFT into the turbulent 1960s.

For four tempestuous decades after its founding in 1919, the California State Federation of Teachers struggled to survive. Finally, after consolidation, organizing and steady growth, the question of whether a state federation could endure changed from “would the CSFT survive?” to “how will the Federation become an organization best suited to serve locals?”

The 60s and 70s

Teachers and classified staff win collective bargaining

In the decades from 1960 through 1990, the union embodied the messy strength of union democracy, leading its locals through social, financial, and educational growth and change. In 1963, the Convention voted to drop the “State” from the union’s name, becoming the California Federation of Teachers.

A succession of effective leaders ensured the survival of the CFT. Lou Eilerman led the CFT into the 1960s, followed by Maurice Englander in 1962, Fred Horn in 1963, and Marshall Axelrod in 1965. Beginning in 1967, Raoul Teilhet would lead CFT for the next 17 years.

Presidents Rust and Eilerman gave the organization philosophical and administrative coherence. Englander supported expansion into the state university and community college systems. Axelrod campaigned for “teacher power.”

During Englander’s term, CFT won mandatory hearings before dismissal for probationary teachers (later lost in SB 813), successfully defended a teacher reassigned for having a beard, and other cases for which the CFT became known as the “ACLU for teachers.”

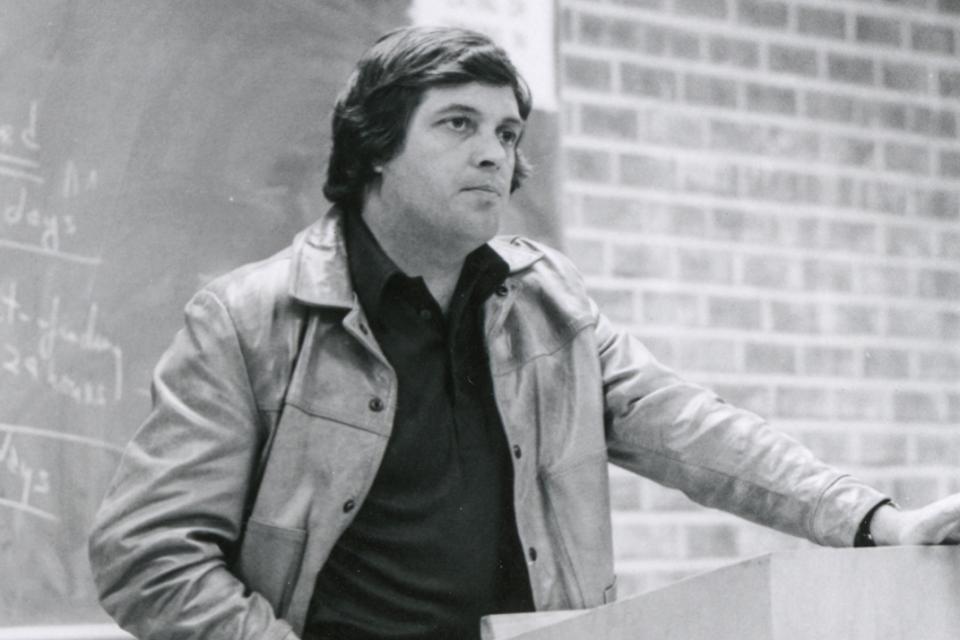

Raoul Teilhet, a Pasadena High School teacher with a charismatic personality and the boundless energy of a spirited organizer, became the first paid full-time president of the CFT. Teilhet was remarkably suited to guide the organization through its period of greatest change and growth.

A political leader in politicized times, Teilhet helped charter dozens of locals. He doubled the size of the union, oversaw the development of a modern union staff, and strengthened the ties between CFT and the labor movement.

Broad social change drove impassioned debate at CFT Conventions — the Women’s Movement, the Civil Rights Movement, and the Anti-War Movement. At the same time, CFT fought for teacher professionalism, probationary teacher rights and intellectual property rights for higher education faculty. The 1960s saw a string of new AFT locals organized in the state university and community colleges. CFT hired more staff, including Legislative Director Mary Bergan.

Even without the protections of collective bargaining, California teachers began picketing and striking. The CFT and other unions organized 10,000 education supporters to march in Sacramento in 1967 when Republican Gov. Ronald Reagan cut education funding.

BUT THE FIGHT for collective bargaining dominated the union’s agenda. After New York teachers won collective bargaining in 1960, California teachers flocked to the Federation and membership grew to 15,000 by 1970.

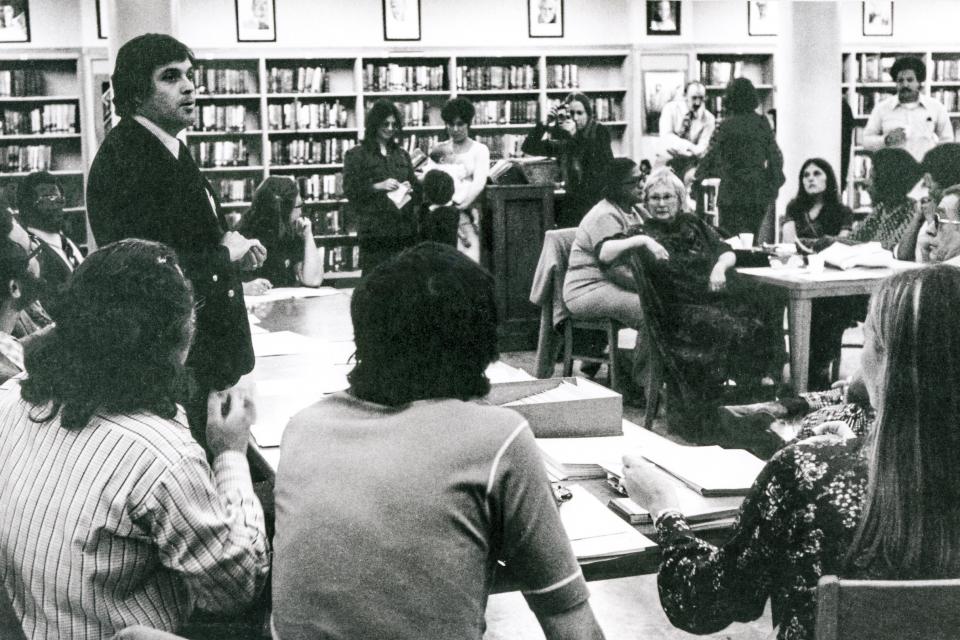

Between 1960 and 1976, CFT introduced a collective bargaining bill in each legislative session. In 1971, the collective bargaining bill got its first full hearing in the California Legislature.

The CFT achieved success in 1976 when Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law the Education Employment Relations Act, SB 1960, carried by a former AFT local president turned state senator, Albert Rodda. Teachers and classified employees in California schools and community colleges had finally won the right to bargain collectively over their conditions of work and wages. A new era in California education unionism began.

The race between CFT and its rival, the California Teachers Association, was on for exclusive bargaining representative status in school and college districts throughout the state. During the next few years, the CFT won dozens of elections, including those in large urban districts, and lost many. By the close of the 1970s, jurisdictional lines had mostly fallen into place for CFT and CTA.

After the flurry of elections, education employees settled down to the hard work of bargaining and enforcing contracts. The growing number of community college faculty in CFT formed the Community College Council, which played a key role in shaping CFT. Paraprofessional and classified locals voted the AFT their bargaining agent after the AFT in 1977 welcomed educational workers other than teachers into its ranks.

In 1978, the Higher Education Employer-Employee Relations Act was signed into law, bringing the benefits of collective bargaining to university employees. UC members had formed the University Council-AFT several years earlier.

The end of the 1970s saw collective bargaining in public education institutionalized, and unionism thriving. There were nearly 150 AFT local unions in California representing 60,000 educators working in public and private schools.

In 1978, however, despite the CFT’s fierce opposition to Proposition 13, voters approved the measure. Conservative Howard Jarvis had persuaded the public that without Proposition 13, seniors on fixed incomes would lose their homes. This vote dramatically changed property taxation and stemmed the flow of revenues to the state and therefore to public education.

The 80s and 90s

The union gains strength, focuses on professional issues

When Raoul Teilhet stepped down in 1985, Senior Vice President Miles Myers was elected CFT president. During the 1980s, Myers carried on the teacher-scholar tradition by researching and writing about professional authority for K-12 teachers.

The classified and paraprofessional group was one of the fastest growing sectors of the AFT then. To ensure distinctive identity for classified employees in the CFT, the union in 1982 created the Council of Classified Employees.

In 1983, UC librarians chose the University Council-AFT as their exclusive bargaining agent, and a year later non-tenure track faculty also chose UC-AFT. However, in a devastating defeat, CFT, which represented several thousand CSU faculty, lost the statewide election for representation by 39 votes in a bargaining unit of 19,000.

CFT’s Community College Council lead the effort to restore funding to the community college system in 1983 when Gov. George Deukmejian cut nearly a quarter billion dollars from the budget. In the latter part of the decade, CFT helped in the passage of a landmark community college reform package, AB 1725.

CFT also instituted trust agreements between K-12 districts and local unions, to negotiate in areas beyond the collective bargaining contract. And in 1989 San Francisco educator unions merged to form the state’s second local union in California affiliated with both the AFT and the NEA (the first being United Teachers Los Angeles in 1970).

By the end of the decade, the union’s field and legislative staff operated from offices throughout the state and AFT locals represented nearly 75,000 education workers in California.

HEADING INTO THE 1990s, CFT had become a robust union representing the diverse interests of thousands of educators. A growing education workforce and aggressive organizing swelled the ranks of union members. The CFT brought thousands of classified employees and adult educators, long left out of bargaining units, into the AFT’s union culture.

As the number of part-time faculty in community colleges continued to soar, CFT maintained its 30-year battle for equity. CFT’s record of advocacy led part-time faculty to join existing AFT locals and form several new ones. By the end of the decade, CFT membership was more than 65,000.

In 1990, Miles Myers resigned as CFT president and Senior Vice President Marvin Katz, from United Teachers Los Angeles, briefly took over.

Legislative Director Mary Bergan was elected the second woman president of the CFT in 1991 (the first being Olive Wilson in 1924). Bergan would guide the CFT for the next 16 years. She became the first CFT president to be elected a vice president of the AFT, signaling a new understanding by the AFT of the key role of state federations in the national organization.

The union continued to focus on professional issues and standards-based education reform, while struggling to keep public education adequately funded. California schools ranked near the bottom nationwide in per-pupil spending, and unions fought back nearly non-stop right-wing attacks. However, California voters showed their support for public education by rejecting vouchers twice in the coming years.

AS ITS RESOURCES GREW, CFT built its capacity to serve locals and members. With 126 AFT locals, running the union and keeping up with myriad issues became more complicated.

Under Bergan, the CFT hired specialists in budget research, training, member benefits, political action, organizing, data management, and education issues to augment the work of field representatives. Public relations raised the profile of the CFT. Union publications became more professional and CFT went online.

State politics always had a heavy impact on the fortunes of the CFT and its members. Eleven years after Proposition 13 gutted state funding for education, Proposition 98 provided a tenuous guarantee of minimum levels of funding for schools and community colleges. CFT always used endorsements and consistent principles to give the union influence far beyond its numbers in state elections.

The 1993 campaign to oppose school vouchers, Proposition 174, marked the first time CFT contributed major funds to a ballot campaign. The union developed a formula for campaigns, helping in 1998 to defeat right-wing attempts to limit union political activity in Proposition 226, and another voucher attempt, Proposition 38, in 2000. The CFT began assisting locals in endorsing and electing candidates for their districts’ boards of trustees.

The Turn of the Century

The Federation rises to demands of the new century

By 2001, state revenues plunged along with tech fortunes, and education was again forced to cut back programs. Every budget since 2002 added new debt and fatally undermined California’s ability to meet the basic needs of its citizens. CFT called for new revenues, fairly raised, long before other educators and unions.

Despite growing activism, the union didn’t always win. Particularly bitter was the recall of CFT-endorsed Democratic Gov. Gray Davis in 2003 and the defeat in 2004 of Proposition 56, which would have ended the budget stalemate in Sacramento that continued until the end of the decade.

In 2005, CFT members mobilized as never before, joining the rest of the labor movement and other progressive groups to defeat Republican Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s three anti-worker measures. Proposition 74 needlessly lengthened probation for K-12 teachers; Proposition 75 tried again to limit union political activity; and Proposition 76 restricted state funding of public services. Members savored the victory for months.

Senior Vice President Marty Hittelman was elected CFT president in 2007, a year before the biggest economic downturn in memory hit CFT members with lost jobs and assignments. With education funding now cut to the bone, the union’s continued call for more revenue became more vital than ever before.

To garner public support, CFT and community allies in the spring of 2010 embarked on a 365-mile march through the Central Valley — the March for California’s Future. The 48-day trek focused attention on the need to restore and maintain a high-quality public education system and other public services, an economy that serves all, and a fair tax system to fund California’s future.

Along the way, marchers talked about how the poorest one-fifth of Californians paid more than 11 percent of their income in state taxes, while the wealthiest 1 percent paid less than 8 percent of their income. They also gathered signatures for the CFT’s ballot measure to replace the two-thirds vote required to approve a state budget with a simple majority vote and end the tyranny of a minority of legislators who held up the budget every year.

That fall California voters agreed, and passed Proposition 25. The union had succeeded in keeping state funding flowing to public education and other services, as it had set out to do six years earlier with Proposition 56.

To the Present Day

CFT leads the way in progressive taxation to fund public services

Joshua Pechthalt, a CFT vice president from United Teachers Los Angeles, was elected CFT president in 2011. A few months after his election, the national Occupy Movement put wealth inequality squarely in the public mind, setting the stage for CFT’s bold Millionaires Tax.

The 2012 measure proposed higher tax rates for the wealthiest Californians — individuals earning more than $250,000 and couples earning more than $500,000 a year — and immediately garnered widespread public support.

The CFT worked in collaboration with Gov. Jerry Brown on the measure that eventually became Proposition 30. Voters approved it, making California a national leader in progressive taxation. Now districts and unions could determine spending without the fear of layoffs, program cuts or eliminations, and student fee increases.

Also in 2012, anti-union forces again sought to limit the political power of unions and put Proposition 32 on the ballot. Despite massive cash infusions from out-of-state conservatives, worker power succeeded and voters rejected the measure, making it the third such defeat since 1998.

But Proposition 30 had an expiration date. Four years later, CFT and its allies put forward a measure to extend Proposition 30. Not wanting a return to austerity, California voters in 2016 overwhelmingly approved Proposition 55. It ensures continued funding for schools and community colleges by maintaining the income tax on the wealthiest Californians through 2030.

In an ongoing fightback campaign, CFT won significant reform of the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges. Through legislative, legal, and organizing actions over a five-year period, members succeeded in turning around a commission that unfairly revoked and threatened loss of accreditation.

The surprise of 2016 was Donald Trump being elected president. Even though California remains largely a progressive bastion, public sector unions face a national threat in the U.S. Supreme Court case Janus V. AFSCME. The case represents yet another anti-union conservative attack that seeks to limit the power of workers and their unions.

The CFT hired organizers and renewed its focus on member outreach, helping local unions to sign up thousands of new members throughout the state. Membership reached 110,000 with 145 AFT local unions in California.

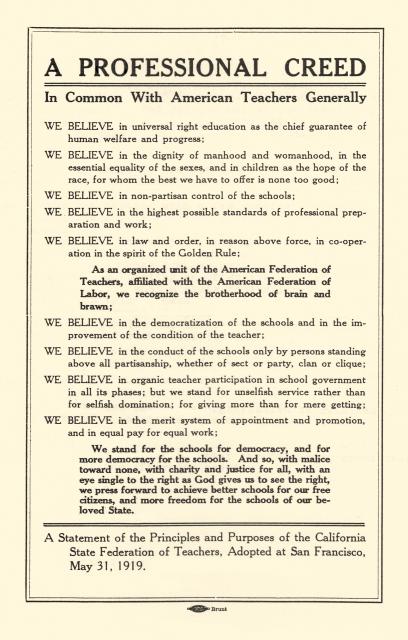

THE TRIALS AND TRIBULATIONS of the past century have demonstrated that the CFT remains true to its first principle in The Professional Creed put forth on May 31, 1919: “We believe in universal right education as the chief guarantee of human welfare and progress.” The CFT is steadfast in its commitment to ensuring high-quality educational opportunities for all Californians, securing fair and equitable conditions for all education workers, and, through progressive action, striving to build a more just society.

> Excerpted from 70 Years: The History of the California Federation of Teachers, 1919-1989 with additional writing by former Communications Director Fred Glass, Publications Director Jane Hundertmark, and former Assistant to the CFT President Elaine Johnson.