The month of October is once again time to give special attention to part-time faculty issues. Officially, Campus Equity Week is the week of October 22-26, but what’s more important is that campus communities get the word out this fall before the legislative process begins.

To assist in this outreach, the CFT Part-TimeFaculty Committee has prepared a toolkit for Campus Equity Week with sample letters, flyers and buttons. It includes resources for working with faculty, students and the larger community.

First initiated in 1999 by COCAL, the Coalition for Adjunct Contingent Labor, Campus Equity Week originated as an idea which put forth this basic idea: have adjuncts, students, and members of the larger academic community join together at one or several activities during a given week, usually the last full week in October, and discuss the unequal working conditions for contingent workers, the effect of the working conditions on student learning and success, and to call for change over a very simple premise — equal pay for equal work.

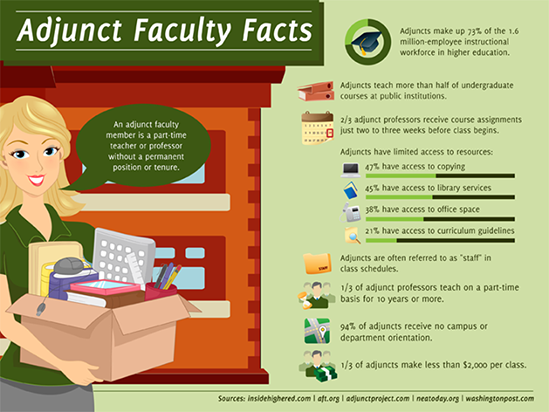

Sadly inequity remains. Part-time instructors are still paid only for their direct contact hours in the classroom, and then at a percentage of what their full-time colleagues make. Further, they are limited by state law to teach no more than 67 percent of a full-time load in a district. The end result is adjuncts making often less than half of what their full-time colleagues earn for the same teaching load.

It is likely that at any given California community college, it is possible to find an adjunct who is either housing insecure, or homeless. Many adjuncts have turned to other professions to support themselves while still teaching.

Many of these so-called “part-time,” or, as the state of California has classed them, “temporary” workers will teach in excess of the 30 LHE (Lecture Hour Equivalent) per year to make ends meet, and some have been doing this for over 40 years. Such instructors are hardly “part-time,” or “temporary.”

And, as a 2015 study by the UC Berkeley Labor Center would suggest, as many as one in four adjunct instructors is on some form of government assistance. It is likely that at any given California community college, it is possible to find an adjunct who is either housing insecure, or homeless. Many adjuncts have turned to other professions to support themselves while still teaching.

Beyond pay inequity, adjunct faculty also face a lack of job security as they are hired on a semester-by-semester, or contingent, basis. Even those adjuncts who enjoy rehire rights language in their local collective bargaining contracts are still “at will” workers.

There are yet other challenges. Many adjuncts lack office space, and are disconnected from their respective departments, which may meet when they’re teaching somewhere else or working with students. Some colleges significantly limit adjunct involvement in shared governance, or highly encourage it, yet offer no compensation for ancillary pay. Adjuncts further struggle with lesser retirement benefits than their full-time colleagues, and female adjuncts are often effectively denied maternity leave pay.

More unsettling should be the fact that adjuncts now roughly represent close to 70 percent of faculty at California community colleges. It’s one thing to say that these working conditions have a deleterious effect on adjunct instructors and their families, which they do. One may also want to consider how they affect students.

Instructors having to teach on multiple campuses are often not available for office hours, or cannot provide hours when it is convenient for students. Further, adjunct instructors struggle to be institutionally connected to any of their campuses or districts, which means they may be unaware of essential resources that struggling students might need from tutoring to mental health services.

Research has shown that students who learn from contingent instructors may in fact have lower academic outcomes. Sadly, many such studies point at the instructors as the problem without considering the larger problem – how adjunct working conditions prevent an instructor from being their best.

Consider the issue of educational equity itself. California community colleges, in comparison to both the CSUs and UCs, teach significantly higher proportions of minority and economically disadvantaged students. Though adjunctification is also an issue in those systems, the level is less than in the community colleges. If California truly aspires to realize equity and student success, it must do better.

First, community colleges could simply follow the law as mandated by AB 1725, passed in 1988, which calls for 75 percent of instruction to be taught by full-time instructors, and 25 percent by part-time faculty. Presently, no California community college is in compliance. California needs to hire full-timers, which it could easily do from an already highly qualified and skilled pool of adjuncts teaching in the system – ones whose students refer to them not as “part-timers,” or “adjuncts,” but “professors.”

Second, and equally important, the colleges need to improve

existing working conditions for part-time faculty. Equal pay for

work in the classroom, pay for office hours, healthcare benefits,

and ancillary pay for committee work and shared governance would

go a long way.

— By Geoff Johnson, member of the AFT Guild, San Diego and Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community Colleges