Eight days after the six-day strike had ramped up public pressure, the Los Angeles Unified school board passed a groundbreaking resolution calling for a moratorium on new charters in the district until Sacramento completes a study of how their unchecked expansion has affected traditional schools. The district also made a significant investment in local community schools.

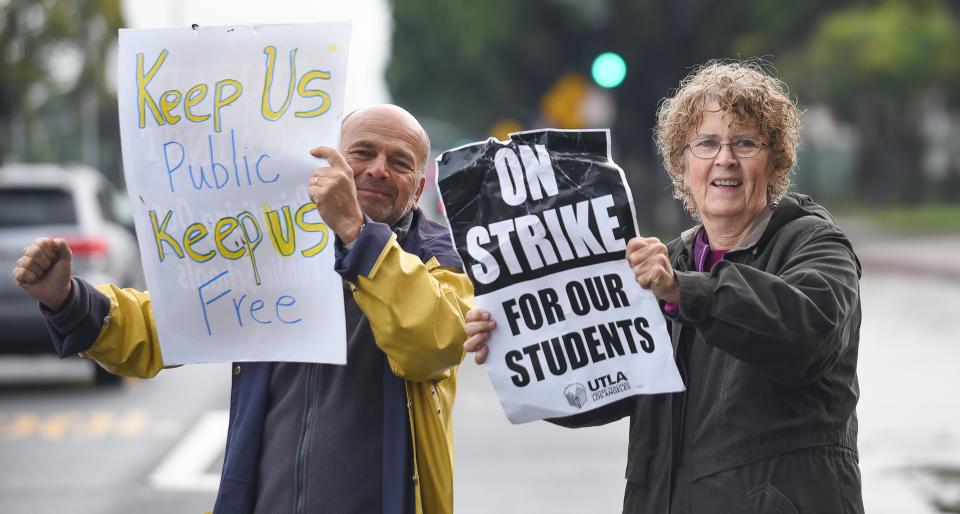

On day two of the UTLA strike, members teaching at a South L.A. charter also walked out, and stayed out until victory two weeks later.

During nearly two years of contract talks, United Teachers Los Angeles and Los Angeles Unified made little progress, and none of the complex issues on the bargaining table reflected clashing philosophies more than charter schools.

In 2000, there were 10 independent charters in the district. Today there are 277, representing the highest concentration of any urban district in the country. One of every five LAUSD students now attends a charter school.

UTLA points to the dizzying growth of charters and underfunding of traditional schools as a double-edged attack on public education. Two of the union’s main proposals were capping the “privatizers” who are seeking more charter schools and instead promoting a “community school” model with greater parent engagement, broadened curriculum, and wrap-around social services.

But Superintendent Austin Beutner, who made his mark on Wall Street, has no education experience. His closest supporters see LAUSD as a failed social institution that should be replaced by charters.

Last November, the Los Angeles Times reported on Beutner’s plan to “re-imagine” LAUSD and carve the 700-square-mile district into 32 school networks, referred to as “portfolios.” Under this Wall Street investment model, struggling schools could be considered “under-performing assets” and closed or converted into charters.

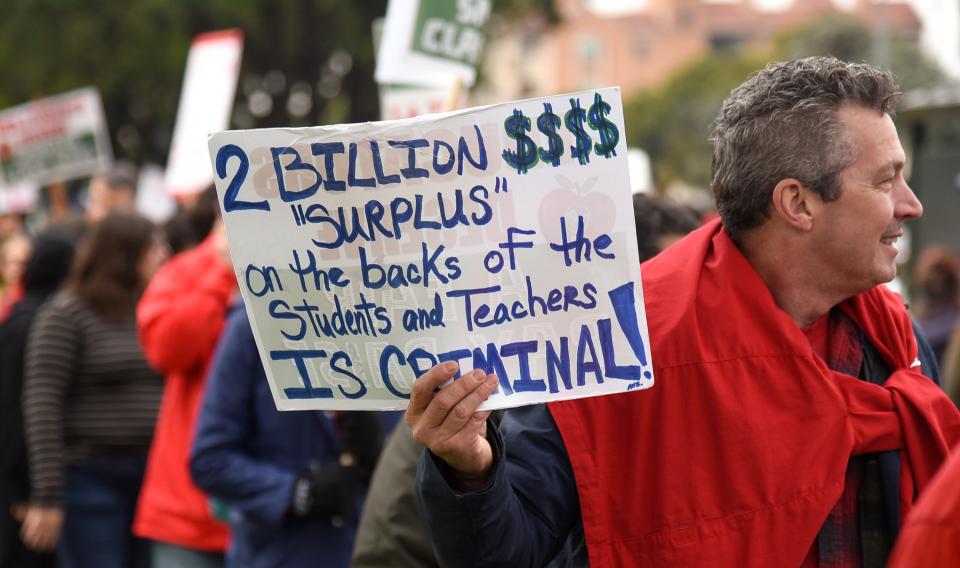

In the weeks leading up to the strike, UTLA began to significantly change the public’s opinion of charters with two numbers.

The first – $591 million – is how much charter schools drained in one year from the district budget, according to a comprehensive fiscal analysis commissioned by UTLA. And the loss was growing.

The second – $1.9 billion – is how large a budget surplus Beutner had to invest in Los Angeles Unified. If he wanted to, of course. Buetner claimed the district faced financial disaster.

Public opinion was clear as soon as teachers struck for “the schools our kids deserve.” Every newscast during the strike offered up reasons to support L.A. teachers, wiping away decades of negative reporting on public education.

Board resolution to Sacramento

Union and district negotiators addressed several non-traditional areas of bargaining, and called on Sacramento to address flashpoints beyond their control.

Both sides agreed that California – currently ranked 43rd of 50 states in per pupil funding – must spend more on education. Gov. Gavin Newsom promised to draw on a surplus left by Jerry Brown for short-term help. Voters could provide long-term funding in November 2020 by passing the Schools and Community First ballot measure, which would close Proposition 13’s tax loophole for commercial property.

UTLA and LAUSD also agreed to seek Sacramento’s help on charters, which are regulated by state law and cannot be negotiated in a labor contract. On Tuesday, January 29, the LAUSD School Board voted unanimously to approve the contract, and 5-1 to ask Newsom and state officials for an 8- to 10-month moratorium on new charters while the state studies their effect on traditional public education.

“This is a win for justice, transparency, and common sense,” UTLA President Alex Caputo-Pearl told the board. “We need to invest in our existing schools, not follow a business model of unregulated growth when new charter schools are fundamentally not needed in L.A.”

The UTLA union contract does tackle one common point of friction between charters and traditional schools. At campuses where “co-located” charters share space with traditional schools, UTLA will now appoint a “co-location coordinator” to provide feedback.

We need to invest in our existing schools, not follow a business model of unregulated growth when new charter schools are fundamentally not needed in LA.

Los Angeles special election sure to tilt school board

Charters are sure to figure prominently in a March 5 special election to replace an LAUSD school board member who was forced to step down. Charter operator Ref Rodriguez pled guilty last year to a felony election finance charge, but wouldn’t resign until the pro-charter 4-3 majority could hire Beutner as superintendent. The board is now split 3-3 between charter advocates and critics.

To replace Rodriguez, UTLA has endorsed Jackie Goldberg, a longtime progressive, former teacher and assemblymember, who began her political career on the school board. With a crowded field of 10 candidates, a May run-off is likely.

California voters show signs of having soured on charters. In November, Tony Thurmond, a strong defender of public education, narrowly defeated charter proponent Marshall Tuck in his second bid for state superintendent of public instruction.

A major investment in local Community Schools

Los Angeles Unified agreed years ago to create a working group to implement local community schools, but went no further with the idea.

“The working group hasn’t even met in six months,” said team member Julie Van Winkle, the union’s North Area regional director.

That’s about to change. Under the new contract agreement, LAUSD will designate 20 community schools by July, and 10 more schools by July 2020. The district will invest $350,000 in each school over two years. Leadership councils will have full discretion over all budgetary items outside of the site council.

Existing local community schools provide rich academic programs that include the arts and STEM classes, as well as medical care and other social services for students and their families.

“But it’s bigger than that,” said Rebecca Solomon. “Community schools give parents a voice in how their school is run.”

Solomon teaches social studies at the UCLA Community School, one of a half dozen campuses where the Ambassador Hotel, a relic of Old Hollywood, once stood in what is now Koreatown. These are, in UTLA’s words, “the schools our kids deserve.”

“This is the positive vision for public education we came up with,” said Solomon, who is also the union chapter chair at the school. “We are committed to funding it, and we know it can be done.”

But it’s bigger than that. Community schools give parents a voice in how their school is run.

UTLA moves to organize charter teachers

Putting a price tag on how much charters drain yearly from Los Angeles Unified stirred a post-strike opinion piece in the Los Angeles Times titled, “I’m a charter school teacher. The LAUSD strike made me realize how I’m part of the problem.”

“I love my school, my colleagues and my students fiercely, and I’m proud of what we’ve built,” wrote Riley McDonald Vaca of Camino Nuevo High School.

“The strike has made me consider how charter school expansion is harming the city,” continued McDonald Vaca, the mother of an LAUSD child. “As more money is invested in new ideas and new campuses, fewer resources and students are left for the many great programs still trying to gain their footing in our current district and charter schools.”

UTLA began to organize charter educators about 10 years ago and have made steady progress. Last year, teachers at three of the 25 schools in the Alliance for College-Ready Public Schools signed their first contract.

The strike has made me consider how charter school expansion is harming the city.

Accelerated Charter Schools launch their own strike

On day two of the UTLA strike, about 80 members at The Accelerated Schools (TAS) in South Los Angeles launched their own strike after more than a year of fruitless contract talks. They staged the first walkout at a California charter and only the second strike by charter teachers in the nation.

Two days later, CEO Johnathan Williams called police when parents and students tried to deliver a petition calling on him and TAS trustees to negotiate a fair contract for teachers. The number of strikers and supporters on the picketlines ballooned in response.

People are scared because anyone can be fired.

Amanda Martinez helped organize TAS teachers in 2008. “Things were so bad that it only took eight days to gather all the signatures we needed.”

Martinez was chapter chair for the first eight years and helped negotiate the first three contracts. The big issues for TAS teachers, she said, are binding arbitration, job security and affordable health benefits.

The turnover rate at TAS is explosive. Teacher Nicholle Hamilton said 40 percent of high school teachers left after their principal was changed with no explanation. “People are scared because anyone can be fired.”

Five of Maria Zamora’s six children have graduated from TAS, and her youngest child is a senior. “As a parent and as a volunteer here, I know they received a good education,” she said.

Zamora worked on parent committees for years, but said many parents feel uncomfortable interacting with administrators. “There is no transparency. The director sends ‘robo-calls’ to parents. They don’t encourage parents to get involved because they want to keep tight control.”

After two weeks of picketing, UTLA and TAS negotiators reached a tentative agreement on Sunday, January 27, that strikers approved the next day by a 77-1 margin. Newly negotiated provisions include:

- Three months severance, including salary and benefits, for any teacher who isn’t offered an employment contract from one year to the next.

- A $10,000 signing bonus for teachers who return to their positions at the beginning of each school year.

- Annual increases in the employer’s share of healthcare costs.

- An improved arbitration process that requires a unanimous vote of the TAS Board of Trustees to reverse an arbitrator’s decision.

— By Steve Weingarten, CFT Reporter