United Teachers Los Angeles has fought for nearly 50 years to give parents a greater voice in how their children’s schools are run. In recent years, UTLA stepped up its outreach by hiring community organizers, building coalitions, and working with supporters in changing neighborhoods.

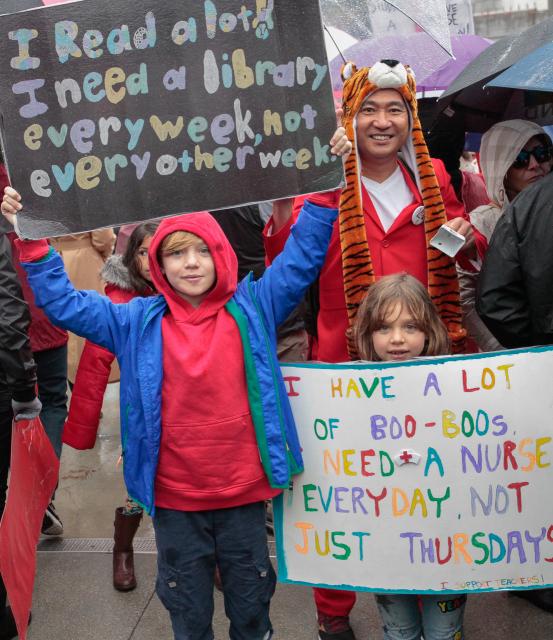

Those efforts bore fruit in January, when thousands of parents joined teachers on picket lines across the 700-square-mile school district to fight for “the schools our students deserve.”

The Los Angeles Times front-page headline on day three of the UTLA strike – “Teachers Bask in Public Support for Strike” – was actually behind the curve. Public opinion was clear from day one.

Parents picketed alongside teachers while community groups joined UTLA rallies in Grand Park and, in a nod to Los Angeles’ fascination with the entertainment industry, progressive celebrities added their voices to teachers’ demands.

The passion behind the outpouring was clear, but organizing parents on that scale wasn’t easy. It took time, resources, and the right people.

UTLA hires two grassroots organizers

Neither Ilse Escobar nor Esperanza Martinez is a credentialed educator but they are the face of UTLA for thousands of LAUSD parents and community activists.

Shortly after teachers approved “Fund the Fight” in 2016, the union invested part of the increased dues in hiring its first two parent and community organizers. Escobar is a “dreamer” and came out of the undocumented student movement. Martinez previously worked with the Bus Riders Union, a civil rights membership organization for the predominantly low-income mass transit ridership of Los Angeles County.

“This is a dream job,” Escobar said. “We come from community organizations that fight for social justice, but we never had this level of strategy or resources.”

Escobar and Martinez began by working with a group of parents fighting KIPP charter schools over co-location with their children’s traditional school.

“I wasn’t sure how much support the parents had,” Escobar said, “but I could see they were for real when they brought more than 100 people to an event we planned.”

UTLA worked with the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment (ACCE), the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy (LAANE), and the group Students Deserve Los Angeles to build the coalition Reclaim Our Schools L.A. (ROSLA).

Parents were also attracted by UTLA’s “common good” demands, from expanding green space and limiting random searches, to providing legal aid for immigrant students.

On day three of the strike, hundreds of ROSLA parents demonstrated in the pouring rain outside the homes of LAUSD Superintendent Austin Beutner, pro-charter school board President Monica Garcia, and charter promoter William Siart. They showed the same militancy as the janitors and hotel maids who sparked a union resurgence in Los Angeles during the 1990s.

“It’s pretty amazing,” Escobar said. “The most vulnerable people are on the front lines of our mobilization. Moms who don’t speak English totally understand privatization.”

ROSLA members were prepared to occupy district headquarters the day after Martin Luther King Day, Escobar said, but called off plans after negotiators reached a tentative agreement.

“UTLA really believes in the work we’re doing,” Escobar said. “We needed the parents’ voice to push the district, and they pushed hard.”

The ROSLA website also features the coalition’s roadmap for educational reform, “A Vision to Support Every Student,” and a bilingual video on the Schools and Community First Act, a ballot measure to close a loophole in Proposition 13 that allows owners of commercial and industrial property to avoid tax increases.

The union added parent and community pages to the UTLA website that feature contract information in Spanish and English, including how each demand will build parent power, and information about L.A.’s special election to fill a crucial seat on the school board. The site also links to We Are Public Schools to showcase videos of Micheltorena Elementary parents standing with teachers.

It’s pretty amazing. The most vulnerable people are on the front lines of our mobilization. Moms who don’t speak English totally understand privatization.

Teachers have a unique bond with parents

The night before the UTLA strike was originally slated to begin, about 200 parents and students filed into the Presbyterian Church in Silver Lake, an older working class neighborhood that now attracts its share of artists and tonier residents.

Thirteen teachers from the local cluster of LAUSD schools were on the stage, ready to answer parents’ questions about the status of negotiations and how they could help UTLA prevail in the coming walkout.

“If this fight was about salary, it would be over. We would have won,” said one of the union chapter chairs, referring to the narrow gap remaining between UTLA and LAUSD proposals on pay.

The bigger fight, however, was still on. All present agreed that LAUSD needed less testing, smaller class sizes, and more nurses, librarians and counselors. It was time to cap private charter schools and their drain on the district budget, and to invest instead in community schools.

Teachers raised enough on a Go Fund Me page to cover the cost of meals for students from low-income families who were not going to “cross the picket line,” but normally would have received free lunches. Parents, meanwhile, had organized a talent show at a local theater to raise money for striking teachers who might face economic hardship. This was a true partnership.

During the strike, the enthusiasm was so contagious at Micheltorena Elementary, one of three primary schools in the cluster, that TV news trucks often broadcast from the Sunset Boulevard campus. Ana Ramos-Sanavio, the UTLA chapter chair at Micheltorena, said neighbors have a tradition of working together.

“Community involvement is key,” she said. “In the dual-language program, parents have an expectation that their kids will be multilingual and exposed to the diversity of life in our community.”

The cluster also includes Ivanhoe and Franklin Elementaries, King Middle School and Marshall High. The five schools used a Google doc created by one of the teachers to stage a “gauntlet” picketline down Sunset.

“And it happened just like that,” Ramos-Sanavio said with the snap of a finger. “Everyone was so enthusiastic that it fell right into place.”

Several weeks after the strike, Ramos-Sanavio was hitting stride on the March 5 special election that could tip a 3-3 tie on the school board between charter school advocates and critics. She was at the Friends of Micheltorena booth passing out campaign literature for UTLA-endorsed candidate Jackie Goldberg on the sidelines of the Marshall High field. Nearby, the schools’ parent soccer teams competed in an annual fundraiser.

Money for school programs is a continuous concern for Friends president Angie Gomez and Erin Ploss-Campoamor, who co-chair the group’s fundraising. Their annual goal was previously $10,000 to $25,000, but needs have grown as Title 1 federal funds dry up. They now raise about $175,000 yearly.

“You have to be inclusive and creative,” explained Ploss-Campoamor. “Other groups charge a flat rate – say $2,000 or $3,000 a year – and you either pay it or you’re looked down on. We created a list of suggested donations based on annual household income, and families looked at it as paying their fair share, based on what they could afford.”

Although Silver Lake’s vibrant mix of residents range from blue collar workers to artists and professionals, 55 percent of Micheltorena students are eligible for reduced or free lunches, and 40 percent of households are under the poverty line.

But, Ploss-Campoamor added, no amount of local fundraising can make up for inadequate state funding. “We’re raising funds for P.E. and the arts. That’s not right. Fundraising should be for enrichment, not the basics.”

We’re raising funds for P.E. and the arts. That’s not right. Fundraising should be for enrichment, not the basics.

Adult students on the line with parents and strikers

Dozens of UTLA members, classified staff and adult education students from the Venice Skill Center marched through downtown together last December, and stayed the course through the shutdown.

“The strike was great for teachers to get out of their silos and talk to each other, and for adult ed teachers to reconnect with K-12 teachers,” said Bob Yorgason, UTLA chapter chair at the center. He worked in “the military industrial complex” until he began his second career teaching computer networking skills in 2001.

“I never planned on teaching,” he said. “In terms of happiness, making the switch was the best move I ever made. I haven’t regretted it one day. On the economic side, it has been a total mess.”

The UTLA bargaining team traditionally includes a member from each of the union’s eight geographic divisions. For this contract, the team included an adult education representative, and UTLA polled special education teachers, early educators and nurses.

“This is the first time I can remember when each group’s special needs were addressed at the table,” said adult teacher and negotiator Matthew Kogan. He called an additional 1.1 percent pay raise for his colleagues “maxed out” at the top salary step a “meaningful, but meager, bump.”

Kogan, also a CFT vice president, explained that split shifts are common in adult education and often mean double commutes, which can be hard for older teachers. That makes seniority in picking courses from the matrix even more important. The district agreed to replace a tenured teacher who retires with another tenured teacher, making it easier to accumulate longevity.

In a city of immigrants, people come to adult education to learn English – that is their gateway to training for a good job with a future. No one is well served if our population is earning minimum wage.

LAUSD once served more than 300,000 adult students annually, but the nation’s second largest adult education program was decimated after the recession. The annual budget was slashed from $300 million to $77 million, and enrollment fell to 100,000 students. There are now about 800 adult education teachers. English-as-a-Second-Language is still the mainstay, but other popular classes are graphic arts and the dental assistant program.

“We fight poverty,” Kogan said. “In a city of immigrants, people come to adult education to learn English. That is their gateway to training for a good job with a future. No one is well served if our population is earning minimum wage.”

— By Steve Weingarten, CFT Reporter