1920s: The Condition of the Teachers

Teachers suffered much more in the 1920s than they do today from the low social status accorded their work. Prompted by abysmal pay, the young American Federation of Teachers demanded a $2,000 minimum annual salary at the end of the decade, and a maximum “…which would provide a cultural real wage enabling the teachers to live according to the requirements of their position.” But low pay was just the beginning of the story leading to teacher unionism. Working conditions and civil liberties in the United States were under widespread attack by ultraconservative forces; the condition of teachers mirrored these broader social problems. Most teachers resented but felt helpless before the serious limitations placed on their academic freedom and job security by autocratic school boards and school administrations. A few brave teachers found ways to challenge these oppressive circumstances.

In 1919 several small teacher union locals founded the California State Federation of Teachers. It was an inauspicious year in which to launch a statewide teachers’ union. Following the end of hostilities in Europe, U.S. Attorney General Mitchell Palmer led government and business leaders in a xenophobic, super-patriotic campaign for “American values.” Law enforcement officials and vigilante groups were encouraged to carry out “Palmer Raids”, mass arrests and deportations which created an atmosphere of terror for immigrant workers and union activists. Conservative newspaper columnists and businessmen utilized Propaganda techniques pioneered during the War to decry gains won by organized labor for workers, labeling anything connected with unions “Bolshevik.” As a result, public opinion in the United States turned against unions, threatening the precarious hold they had achieved in American social life. Palmer and his associates singled out the radical Industrial Workers of the World (also called the IWW or the Wobblies), which proclaimed its dedication to the principle of “one big union” for all workers, for especially harsh treatment. Numbering less than a hundred thousand, the IWW nonetheless exerted a militant influence on many more industrial workers in significant areas of the country. Wartime patriotic fervor and its aftereffects helped make the Wobblies’ anti-militarist stand on the United States’ entry into the European conflict in 1917 an easy target for their anti-union opponents. By the mid-20s the IWW’s leaders were in prison or deported, its membership decimated.

In such a political climate, powerful employer groups easily destroyed the steelworkers union, some quarter of a million workers, after a disastrous strike in 1919. A creative variety of intimidation, company unions and paternalistic corporate welfare plans discouraged further organization. Even moderate craft unions of the American Federation of Labor- to which the young teachers’ union belonged- could not escape the anti-union backlash. Hundreds of foreign-born workers were deported, thousands of activists jailed, and some even lynched during the Palmer era, a historical forerunner of the McCarthy era “red scare.” For the next decade and a half a smaller, embattled union movement struggled to survive, barely able to provide minimal protections to workers.

The “Jazz Age” decade did provide some working Americans, including teachers, with a glimpse of the consumer society to come, before it was buried for a while beneath the Great Depression. Mass production industries began to produce vast quantities of household items. Advertising for the good life of consumables soon filled the gaps between programs on the new entertainment medium, radio. For those with more limited visual imagination, movies portrayed the lavish lifestyle possible, if only one possessed enough money to attain it. But for most workers and their families, consuming these images was as close as they could get to living such a life; the weak state of the unions ensured that middle class lifestyles remained out of reach. The ‘Jazz Age’ wasn’t so jazzy for working people in the ‘Roaring Twenties’.

It is difficult to imagine today the level of intimidation experienced daily by classroom teachers of the early decades of this century. Teachers were often fired merely for offering criticism to a principal or administrator. For instance, Dr. Henry Linville, later to become the first president of the New York City Teachers’ Union, asked the New York City Superintendent of Schools, William Maxwell, in 1905, “Do you think that there are no conditions which might justify a teacher in complaining of his superior?” responded Dr. Maxwell “Absolutely none.” Arbitrary administrator decisions affecting teachers were rampant. There were virtually no uniform salary schedules. Teachers at schools within the same district, or even teachers within the same schools, received wildly divergent pay despite similar or identical qualifications; the criteria were solely those of the Principal’s whim.

Older teachers were often released, and younger teachers, presumably willing to accept less pay, were hired to replace them. Friends and relatives of school board members and administrators commonly gained teaching jobs ahead of more qualified applicants.

Once hired, teachers discovered no sanctuary in their classroom; and the source of disruptions to teaching was not limited to the immediate school environment. The 1925 Scopes Trial in Tennessee, deciding whether teachers might instruct their students about Darwin’s generally accepted theory of evolution, represented merely the tip of a large and dangerous iceberg threatening the ability of teachers to carry out their work without interference.

Centralized textbook selection, institutionalized in the years after the World War, took decision making out of the hands of teachers to ensure that the proper “patriotic attitudes” would be instilled in the children of immigrants. Emboldened by the generally anti-civil liberties atmosphere of the era, many states passed laws hindering the exercise of teachers’ constitutional rights. The “Lusk Laws” in New York, for example, declared in 1921, that

“In entering the public school system the teacher assumes certain obligations and must of necessity surrender some of his [sic] intellectual freedom. If he does not approve of the present social system or the structure of our government he is at liberty to entertain these ideas, but must surrender this public office.”

Local school boards presented teachers with a creative variety of restrictions on their teaching methods, content and political expression. At the same time, school boards often gave carte blanche to corporations to make presentations to classrooms on matters affecting their products, while denying access to opposing points of view. Responding to questionable school board practices, Professor Paul Douglas (later Senator from Illinois) asked a fundamental question at the 1929 AFT national convention: why was educational policy “…allowed to be determined by vaudeville promoters, and real estate agents, and lawyers, and bankers, every interest in the community sitting on school boards, except teachers?”

Control over teachers inside the classroom apparently didn’t satisfy autocratic administrators’ urges. School boards sought to expand their dictatorial powers to their employees’ private lives, and fired teachers for infrequency of church attendance, failing to vote, or not turning out at the local Liberty Bond parade. Many school districts dismissed women instructors for such serious infractions as wearing the “wrong” clothing and hair styles, being over forty, and the ultimate sin – getting married. Individual contracts, in those days before collective bargaining, often specified that marriage constituted grounds for immediate termination. If teachers managed to make it through a career, retirement benefits were paltry.

Given these problems, it seems remarkable that anyone went into the “profession” at all. Those who did choose teaching for their occupation quickly ran up against the contradiction between the label “professional” and the rather more sordid reality. It should not be surprising, at least in retrospect, that at some point something had to break. The final straw that pushed many teachers beyond previous limits on their thinking and actions was a wave of attacks by school boards, inspired by the Palmer mentality, on individuals and groups of “unpatriotic” teachers.

The situation clearly was intolerable, and some teachers realized it was not about to get any better without a union.

The National AFT

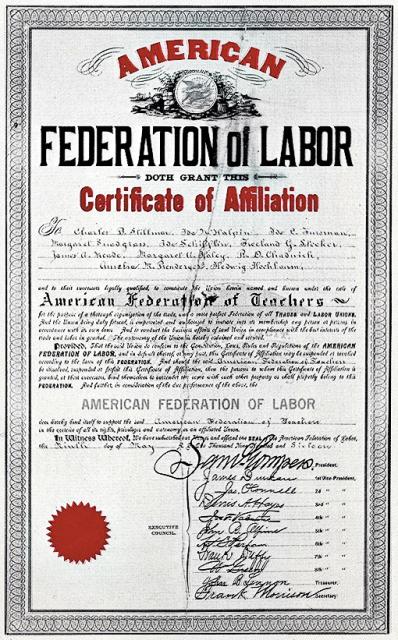

Founded in 1916, the American Federation of Teachers rose upon the foundation of earlier teachers’ struggles for control over their lives and work. In particular the Chicago Federation of Teachers, led by firebrand organizer Margaret Haley, set an impressive example for teachers across the nation in the early years of the century. In both Chicago and New York the founders of the union organized on a platform calling for corporations to pay their fair share of taxes to support education, along with direct advocacy for teachers. The leaders of the fledgling of AFT decided to affiliate with the craft union-oriented American Federation of Labor (AFL) to utilize organized labor’s greater numbers (at that time, around 5 million members) and financial resources in the struggle for improved conditions for teachers and schools.

The AFL practiced a type of unionism that emphasized pride in craft and valorized skilled labor over unskilled work. Its appeal to the largely middle class women teachers hung on a thread of common interest. Members of the AFT, conscious that they worked among the children of the working population, recognized the potential power in an alliance with the parents of their students, both for themselves (economically) and for their charges (politically).

Labor, for its part, felt teachers to be a natural ally, at least in one respect. The longtime president of the AFL, Sam Gompers, undoubtedly articulated the feelings of his rank and file when he made his famous statement regarding labor’s program:

We want more schoolhouses and less jails; more books and less arsenals: more learning and less vice; more constant work and less greed; more justice and less revenge.

The first unions recognized early in the 19th century that workers’ children needed to learn to read and write in order to participate politically in the new republican society. By the latter part of the century, labor saw that its young people could gain greater social and economic opportunities only through a strong system of mandatory public education. Schools served the additional practical purpose of getting children out of the factories, where their presence drove down the wages of adults. Once the unions succeeded in getting child labor laws passed, living wages would become more attainable. But most significantly, children would come off the streets and out of the factories to acquire the basic tools for participation in a democracy.

Not all AFL leaders were supremely happy at the prospect of teachers in their ranks. Some of the more conservative among them, especially in the building trades unions, were quite willing to support public education, but drew the line at calling teachers “brothers”, or — even worse — “sisters”. The somewhat tenuous early connection between teachers and organized labor, varying by geographic circumstance and local cultural traditions, gradually grew more solid over the years.

After several resounding defeats in post-World War I strike, the AFL urged public employee unions to renounce strikes. This was essentially a strategy for survival. AFT leaders accepted Gompers’s cautious approach, and maintained, mostly for the sake of public acceptance, that its locals would never be drawn into a strike. The union’s positions probably represented the limits of teacher action in the containing conditions of the post-war decade. Indeed, even with the polite methods espoused by the AFT in the 20s, barely one fifth of the locals chartered since 1916 were still around by 1927.

If relatively conservative by pre-World War I union standards, the AFT’s positions in the 20s were positively radical in comparison with many of those taken by the National Education Association. By far the larger organization, the NEA had existed for nearly sixty years when the AFT received its AFL charter. Contrary to its claims to represent teachers, however, the Association was dominated by school administrators, who consistently refused at the school site and in legislative efforts to support teachers where it would count: by sharing in decision-making, granting larger salaries, and throwing their weight behind pro-teacher legislation. The first president of the AFT, Charles Stillman, argued, “Experience has shown during the last half century that any organization admitting school officials has rapidly become an organization primarily of, by, and for such officials.” The early development of the AFT in certain crucial respects was defined by its differences with the NEA, and it was on the basis of those differences that the union recruited its membership.

Administrators and boards of education were fond of reminding underpaid teachers that theirs was a vocation of self-sacrifice for the greater good of the public. This appeal was made especially to women – the overwhelming majority of teachers – who were admonished that it was unfeminine to make trade union-like demands for higher wages. Undaunted, AFT teachers pioneered in the movement to convince the public that well-paid teachers were more likely to devote themselves to their calling. The logic of this position brought the AFT to the principle of “equal pay for equal work” long before it became a popular slogan, a crucial proposal for an organization and occupation with a majority of women.

After World War I the union defended three socialist anti-war teachers from New York City despite tremendous pressure to conform to the wave of patriotic fervor in the war’s wake. By way of intimidation the New York legislature formed a committee to investigate “subversion” and included the AFT as one of its targets. The legislature, over the opposition of the AFT, passed what were known as the Lusk laws, which demanded loyalty oaths and provided for the easy dismissal of teachers. Fortunately, the popular Governor of New York, Al Smith, rode into office in 1923 on a platform that included repeal of the restrictive laws.

Two years later the young union turned its attention to another academic freedom case in Dayton Tennessee, where a high school science teacher, John Scopes, was tried and convicted of teaching Darwin’s theory of evolution. The Scopes trial helped the union to sharpen its thinking about academic freedom; it worked together with the ACLU to defend Scopes. The 1925 AFT convention resolved that “It is our belief that the Tennessee anti-evolution law is a menace not only to educational and religious liberty, but to political liberty as well.” Unflinching defense of academic freedom, whether the threat came from courts, administrators, clergy or corporations, remained a hallmark of the AFT; it consistently fought for freedom of expression against what it termed “the invisible government.”

The fight for tenure laws preoccupied the AFT throughout the 20s. Few states had passed tenure bills at that time. One exception was Illinois, where Margaret Haley had lobbied a law in 1917 that contained the first teacher tenure provisions in the country. AFT literature on the issue closely prefigured the laws that were eventually passed elsewhere. The union’s conventions were filled with discussions about how to achieve tenure, the efficiency of a two-year probationary period, dismissal procedures, representation and the like. By developing this expertise and creating statewide legislative committees supported by organized labor, the AFT exercised an immense impact on subsequent efforts to achieve tenure laws.

John Dewey’s AFT membership supported the notion that the union represented the farthest frontiers in thinking on education. Issued AFT membership card #1, the progressive philosopher and Columbia professor lent his prestige to AFT organizing efforts, spoke out on the importance of teacher unionism and participated actively in union affairs. His article “Why I am a Member of the Teachers’ Union” was reprinted and widely distributed.

Equally far-sighted was the AFT’s demand for teacher participation in educational policymaking. Dewey had stated in 1928 that teachers were public servants, and therefore beholden more to their mission to educate than to local school boards. Earlier, at the 1925 convention, the union had proposed “the establishment of Teacher Councils controlled by the teachers and participation in the determination of educational policy.” A few years later the AFT reached a more directly political decision to attempt where feasible to exercise democratic influence over school boards through the ballot box. Dewey coined the slogan “Education for Democracy”, to illustrate the union’s belief that teachers needed to be politically active themselves if they were to effectively teach children the essence of democracy.

Although the AFT was not yet in a position to bring many of these ideas to fruition, their presentation and propagation represented an enormous step forward for classroom teachers. Where there are ideas there is hope, and the AFT was preparing itself to transform the ideas into reality.

California State Federation of Teachers

Olive Wilson, later the third president of the California State Federation of Teachers, began teaching in 1880, and taught elementary school in Vallejo starting in 1900. In 1918 she helped found the first local of the American Federation of Teachers in California, Local 26.

A few months after its formation in early 1919, the San Francisco Federation of Teachers, AFT Local 61, hosted seven other newly chartered AFT locals, including Vallejo, from around northern California in a meeting to discuss the creation of a state federation of teachers’ unions. (It is possible that a representative of the then-secret Los Angeles Local 77 attended the event. Anti-union feelings ran so strongly on the school board that open union membership was equivalent to a dismissal notice.) At that meeting on May 31, the representative of these eight small but determined organizations decided to found a state federation for two stated purposes: as an information clearing-house for locals, and to give teachers a means to express their opinion on statewide education matters.

An unstated reason for the emergence of a state teachers’ federation was the need for mutual support among locals in sometimes dire circumstances, California was especially hard-hit by Attorney General Palmer’s hunt for “subversives.” Teachers were taunted, publicly humiliated and fired for expressing mildly dissenting views from those of ultra-patriotic groups. Paul Mohr, longtime SFFT president and a statewide president in the late 20s, looked back to the founding of his organization in the June 1927 American Teacher, and recalled that its objectives, left out of public statements at the time, also included “to bind the young locals firmly together against attacks from enemies of the teacher-union movement” and “to build up a central fund for the defense of any teacher suffering unjust treatment at the hands of local school officials.” An important factor making the new organization possible was the infusion of veterans back from World War I willing to stand up for themselves and exercise some leadership against intimidation.

In October 1919 the locals met once more in San Francisco and the California State Federation of Teachers (CSFT) was born, with Samuel G. McLean, a Sacramento High School teacher, elected its first president. Olive Wilson was elected vice president.

The new organization boasted just under 800 members at its birth. Recruitment exceeded everyone’s expectations at first, and hopes were high for rapid expansion. No one could have foreseen that despite principled and often heroic battles fought by the CSFT on behalf of its colleagues, little headway would be made in expansion of the statewide organization’s numerical strength for more than two decades.

From the outset the center of the union was northern California. Except for the chartering of Local 77 in Los Angeles, which in any case was driven out of existence by the late 20s, no southern locals appeared until the mid-30s. Membership numbers fluctuated wildly in some locals from year to year due to recurring bouts of administration and civic pressure, and inconsistent resolve on the part of the teachers. A worse problem confronting teachers willing to organize was the common disappearance of the entire locals shortly after chartering. Of the ten California locals that appeared in 1918-19, only Sacramento and San Francisco still thrived by 1930. Several more had arrived on the scene in the meantime, but their hold on life remained tenuous.

Locals sometimes went under for reasons other than intimidation. On occasion the mere threat of a union caused school boards to come up with various improvements, just to keep the union out. One member of the secret Los Angeles local in the mid-20s reported that upon hearing of a meeting called by a national AFT organizer, the school board met immediately and voted a raise for all teachers. Victims of their slight success, a few locals secured immediate demands and promptly folded.

Despite all these problems the CSFT and its members persevered. Beyond sheer survival in a hostile environment, the organization could point to credible accomplishments. One important activity, absolutely crucial to its viability, was building links with the rest of organized labor. In fact, the San Francisco and Sacramento locals succeeded where many of their colleagues failed in large part because of their fortunate births within cities sporting solid labor movements, which protected and nourished the AFT locals.

Of course, in 1919 teacher affiliation with labor itself was seen as a threat by conservative school administrators, government officials, newspaper publishers, and captains of industry. The San Francisco Chronicle in December 1919 complained that “outsiders” were agitating among the teachers, and the S.F. school board passed a resolution in April 1920 forbidding teachers to join any organization “having the power to call a strike or a walkout” – despite the express disavowal of the strike weapon by Local 61’s constitution. If it knew about this disclaimer, the Board ignored it in favor of the higher calling of the union bashing. Teachers fearing for their jobs dropped their membership. The Labor Council attempted to pressure the Superintendent, a member of the musician’s union, to get the Board to rescind its proclamation, but to no avail. The Board did, however, back down from its threat to fire any union teacher.

More promising displays of the merits of affiliation occurred at about the same time. CSFT President McLean reported in the February, 1920 American Teacher that two teachers suspended by the San Francisco School Board were reinstated thanks to the Labor Council, which, at the request of the SFFT, sent representatives to reason with the Board. Labor support was also instrumental in passage of the 1921 state tenure law. One of the most progressive in the country at the time, it provided for a public hearing and representation by council at dismissal after two years probationary teaching. McLean and the SFFT’s Mohr worked closely with California Labor Federation president Paul Scharrenberg to ensure passage. Unfortunately, the law was amended in 1927 to exclude teachers in smaller districts, and hostile forces continued to chip away at it throughout the next decade.

With the labor federation’s assistance the CSFT pushed a bill to triple teacher retirement pay – stuck since 1913 at $500 per year – passed both houses of the state legislature, only to be vetoed on the governor’s desk. Despite this setback, McLean said that “An important thing from the union standpoint, however, has been the recognition of the State Federation as a definite factor in the educational work of the state.”

In San Francisco and Sacramento the teachers unions pulled together committees to survey salaries across their cities. In San Francisco particularly the local received favorable publicity for its efforts at a “scientific” survey, funded by an assessment of its members.

The CSFT helped a number of teachers in legal suits, mostly for wrongful dismissal. In Santa Cruz, Albany, Fresno and other places the state union did what it could to assist teachers to win through the courts what it could not achieve through local strength. The most successful legal effort seems to have been in Fresno, where, following several teachers’ dismissal for “incompetence” a libel action against the Superintendent was undertaken and won.

In at least one city where the Federation was strong, Sacramento, teachers achieved, albeit briefly, a measure of shared governance. Boasting a high membership in the early years of the decade, the president of Local 31 was invited by the Superintendent to consult with him on forming teacher-management councils for important decision making matters. The council was formed; unfortunately, available records do not reveal for how long it existed.

Writing in 1927, Paul Mohr believed that “perhaps the greatest service that the State Federation has rendered the teachers of California and of the United States has been to force some democratization at least of the old-line orthodox teachers’ associations”. As a result of the arrival of the AFT in the education picture, “The class-room teacher has been given some recognition in the deliberations of general teachers’ associations; he has even been allowed to have a separate class-room organization as superintendents have had all along and here and there he has been given the privilege of sitting in on Councils of Administration.” Mohr lamented that new teachers didn’t know this history; they thought, rather, that the small measure of input allowed them in the national Education Association and its councils had always been there, instead of pressured in to being by the AFT.

The first decade of the California State Federation of Teachers ended with considerable less to cheer about than its beginning. Membership has fallen off to a few hundred hardy souls, and of nearly twenty locals charted before 1929, only seven remained; several of these existed mostly on paper. Worse, no new locals had been chartered at all between 1921 and 1928. The political atmosphere had taken its toll, and deep-seated prejudices against women, unions and teacher organization combined to sap the energies of all but the most devoted CSFT adherents. Yet all was not gloom. The new organization had established itself as a voice for teachers; it has forged its bonds with labor, the bedrock of its social support; and it had survived. In the following decade it was hard-pressed to maintain even these modest achievements.

Contract from a North Carolina town in 1930s

I promise to take a vital interest in all phases of Sunday-school work, donating of my time, service, and money without stint for the uplift of the community. I promise to abstain from all dancing, immodest dressing, and other conduct unbecoming a teacher and a lady. I promise not to go out with any young men except insofar as it may be necessary to stimulate Sunday-school work. I promise not to fall in love, to become engaged or secretly married. I promise not to encourage or tolerate the least familiarity on the part of my boy pupils. I promise to sleep at least eight hours a night, to eat carefully, and to take every precaution to keep in the best of health and spirits in order that I may better be able to render efficient service to my pupils. I promise to remember that I owe a duty to the townspeople who are paying my wages, that I owe respect to the school board and the superintendent that hired me, and that I shall consider myself at all times the willing servant to the school board and the townspeople and that I shall cooperate with them to the limit of my ability in any movement aimed at the betterment of the town, the pupils, or the schools.