As they have for the past two years, lecturers at the University of California continue their effort to get the administration to bargain a fair contract. The last agreement between the university and the University Council-AFT, expired on January 31, 2020. The union’s negotiating committee has met with UC’s bargaining team on 50 occasions, yet the four most fundamental issues are still outstanding — high turnover rates, lack of performance reviews, widespread uncompensated labor, and compensation itself.

Contract bargaining, which went on all through the pandemic, has now taken on additional importance, however. The nine-campus system is resuming in-person instruction, and lecturers, who run the most risk of infection because of close contact with students, are also trying to win agreement about how this change takes place.

“Negotiating over the return to in-person classes is happening within the larger context of contract negotiations and our whole relationship with the university,” charged Katie Arosteguy, UC-AFT vice-president for contract enforcement. “The way the administration is treating this continues the same total disrespect for us they’ve shown all along.”

The lecturer bargaining team met with negotiators from the UC Office of the President in July to talk about campus reopenings. In her bargaining update, Mia McIver, UC-AFT president, enumerated the union’s objectives: “to ensure the health and safety of lecturers returning to in-person instruction, compensation for any increase in workload associated with pandemic-related teaching arrangements, and paid leave for lecturers who contract COVID or who have family members who do.”

The university did accept four union proposals. The university will follow public health guidelines about masking, ventilation, testing, contract tracing, vaccination and other issues; it will give fair consideration to lecturers who request alternatives to in-person instruction; and it will provide masks. If a situation arises in which students, faculty or staff don’t comply with safety protocols, and the lecturer takes reasonable steps for health protection, the university agrees it will not discipline or refuse to re-appoint her or him.

“This allows us to make what in our judgment is the best decision should someone else’s failure to follow campus protocols put us at risk,” McIver explained.

Nevertheless, university negotiators refused to come to agreement about some of the issues that have the sharpest impact. While lecturers and faculty with full-time appointments are eligible for sick leave if they or a family member contracts COVID, lecturers with less than 66% appointments are not. The administration has rejected the union’s proposal to extend coverage to them.

Likewise, UC has repeatedly refused to consider a proposal to give lecturers the same family-friendly work arrangements it currently offers to Senate faculty. Most lecturers are women, and the university seems blind to their possible need to teach remotely if a child gets the virus, as has already happened.

Lecturers and contingent faculty at other institutions, even community colleges, have been able to bargain for extra pay for the work involved in setting up online classes during the pandemic. The University of California, despite its wealth and prestige, refuses to consider it. This is not only the subject of ongoing negotiations, but of an unfair labor practice charge.

“People have to buy stuff from home to teach there, everything from upgrading their internet to furniture,” said Arosteguy. “Even more important, lecturers are spending many hours on the increased workload involved. They have to go to trainings, learn the online platform, and give additional help to students they’d have seen before in office hours.”

The union proposal for pay to cover this actually cut in half full compensation for the number of hours lecturers were reporting. When the university still refused to discuss it, the union filed an unfair labor practice charge and the Public Employee Relations Board then issued a complaint.

“What we heard across the table was that we never had to do this extra work, and that they didn’t believe that we ever even did it,” Arosteguy recounts. “We tried to explain this work in detail. Their negotiators heard countless hours of testimony describing the effort people were putting in. But they really have no idea at all of what happens on the ground — a bad case of selectively not hearing what they don’t want to hear.”

Failure to compensate lecturers for the extra work (in effect, wage theft) is not the only unfair labor practice charge made by the union. Others involve the administration’s refusal to bargain over the effects of laying off physical education lecturers at Davis, failure to hold new employee orientations at Irvine, and modifying staff titles at Santa Cruz without bargaining. The pile of charges has grown so high that the university has suggested resolving them all together, a proposal the union is currently considering.

At the same time, however, a new grievance is brewing because each campus is issuing letters of guidance over how to deal with the start of in-person classes, and again failing to bargain over them. At Davis, for instance, an FAQ tells lecturers that if they or a family member gets sick, requiring quarantine, they must find a substitute. That’s a violation of the contract. So is telling lecturers to buy masks for students. And again, when it tells lecturers to be prepared to “pivot to online” it fails to account for the preparatory work needed, much less compensate for it.

Rahul Neumann has been teaching the sitar in UCLA’s music department for a decade, and is worried about unanswered questions about the imminent startup of in-person instruction. “It’s important to be back in person,” he says, “but what do we do if someone is exposed to the virus? What process do we follow? We know the whole country is going through this, but it’s a little late not to have the answers to basic questions.”

Neumann has already had to modify his normal way of teaching, which would previously involve physically guiding students in how to sit and hold their instrument. “So there are clearly changes now, and I will make sure we keep our social distance. I think it’s good to err on the side of caution. But they’re telling us everyone will be tested three times a week, so what happens if someone does test positive?”

Neuman also feels the university should have provided extra compensation over the transition to online instruction last year. “Whatever changes we have to make this year, we know they have no plans to pay for that either. I’m also one of those instructors teaching less than 66% time, so I wouldn’t get COVID-related sick pay if I got the virus. I don’t think that’s fair.”

Meanwhile, as the return to the classroom unfolds, lecturers are escalating their effort to get a contract. The bargaining team gave UC negotiators their final proposal in May, and the administration’s response on June 15 failed to address the four core demands. Three days later the union gave PERB its request that it find that the bargaining had reached impasse. PERB then appointed a mediator.

Tiffany Page, vice president of the UC-AFT lecturers bargaining unit, said that while details about mediation are not public, “what I can say about it is that the mediator has been going back and forth between our team and the UC team trying to see if we can come up with contract language that both parties can agree to. Our concern is always making sure there aren’t loopholes bad actors can use to circumvent the intent. The mediator has not yet called for fact-finding, and we haven’t had any bargaining sessions since we went to impasse.”

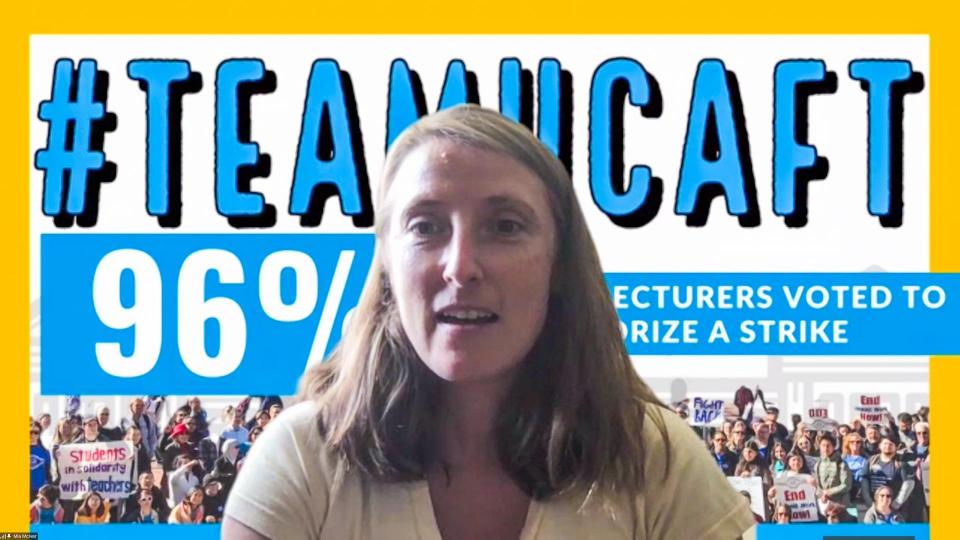

The union already took a vote to authorize a strike in April. A majority of lecturers voted, approving it by 96%. If no agreement is reached in mediation, the mediator can call for fact-finding. A panel of three fact-finders (one appointed by the union, another by the university, and a third by PERB) then makes a recommendation for a settlement. If it’s rejected, the university can implement its last offer, and the union can strike, with a legal protection against permanent replacement by strikebreakers.

“We will continue to organize and leverage every possible pressure on UC administrators before we get to a strike,” McIver warned, “but it’s possible that nothing less than a strike can stanch the brain drain that is depriving talented, qualified, and experienced lecturers of stable employment and fair compensation.”

— By David Bacon, CFT Reporter