For Belinda Lum, sociology professor at Sacramento City College and chief negotiator for the Los Rios College Federation of Teachers, it was because she’s the granddaughter and great-granddaughter of people who came over from China with fake papers. For Leis Rodriguez, it was wanting to use her law school degree for her passion and becoming an immigration attorney.

And Sandra Guzman, a counselor at Sacramento City College, recalls her parents saying yes when the priest asked the congregation if anyone could take in three refugees from El Salvador. She wasn’t thrilled to give up her room and share with her sister, but she loved teaching her new guests English and she talked about her excitement when she coached the girl staying with them to say “Yeah,” instead of “Yes,” so she would sound like the other kids.

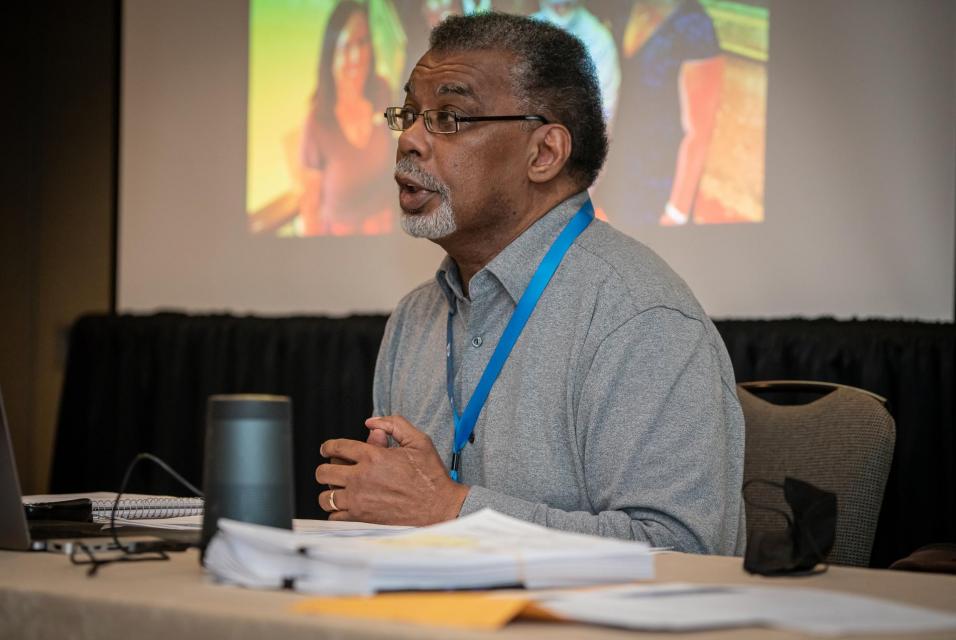

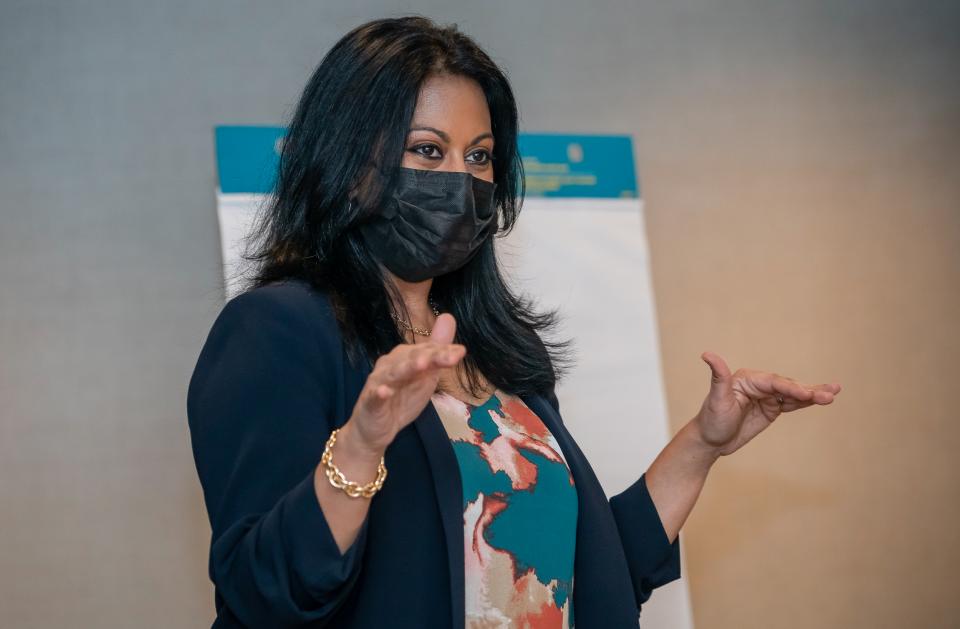

These were the reasons the three leaders of the workshop “Supporting Our Undocumented Community: A Call to Action,” gave for wanting to work with undocumented students.

In the workshop, the trainers handed out stickers and cards with “Don’t be a dream crusher, be a hope dealer,” and took participants through some of the challenges undocumented students face as well as some ways to transform and influence their future.

Attendees did a writing exercise, imagining they were 21 and had been in a relationship for a year and were thinking about disclosing their undocumented status. What would be some reasons for that? What kind of emotions would come up? And what were some possible consequences?

After writing, the participants discussed their answers: wanting to travel, explaining why they didn’t want to go to a protest or couldn’t travel to their home country, considering moving in together or getting a job might be reasons to disclose undocumented status. Emotions? They included fear, frustration, anxiety, and hope.

The workshop leaders also went over some of the terms, such as undocumented; DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), a policy announced by Barack Obama in 2012, meant to protect youth who came to the United States when they were children from deportation; and AB 540, which authorizes undocumented students who meet specific criteria to pay in-state tuition at California’s public colleges and universities

They also covered laws affecting education and undocumented students, and challenges in higher education, such as navigating institutions, being hesitant to fully engage in campus life, gaps in financial aid, and limited internship or work opportunities.

Guzman said she sees the anxiety in students who come to see her and tries to allay it.

“I say, ‘Sit down, welcome, I’m glad you’re here,’ and I ask them, ‘What is your dream?’” she said. “It shifts the energy. I say, ‘Your job is to follow your dream, my job is to insert hope.’”

Guzman has been working at schools long enough to see that laws do change. She told a story of a student who came in years ago, wanting a business degree but thinking it didn’t make sense for her since she was undocumented. Guzman encouraged her, and that woman went on to Chico State and got her business degree, and now she works in the state chancellor’s office leading efforts for undocumented students.

Being a hope dealer is important but not a strategy for change, Lum said, and she talked about things unions could fight for in collective bargaining, such as re-hire rights, security of employment, and healthcare benefits.

“Unions have a lot of resources,” Lum said. “One of the most important things is having allies in the right places.”

— By Emily Wilson, CFT Reporter

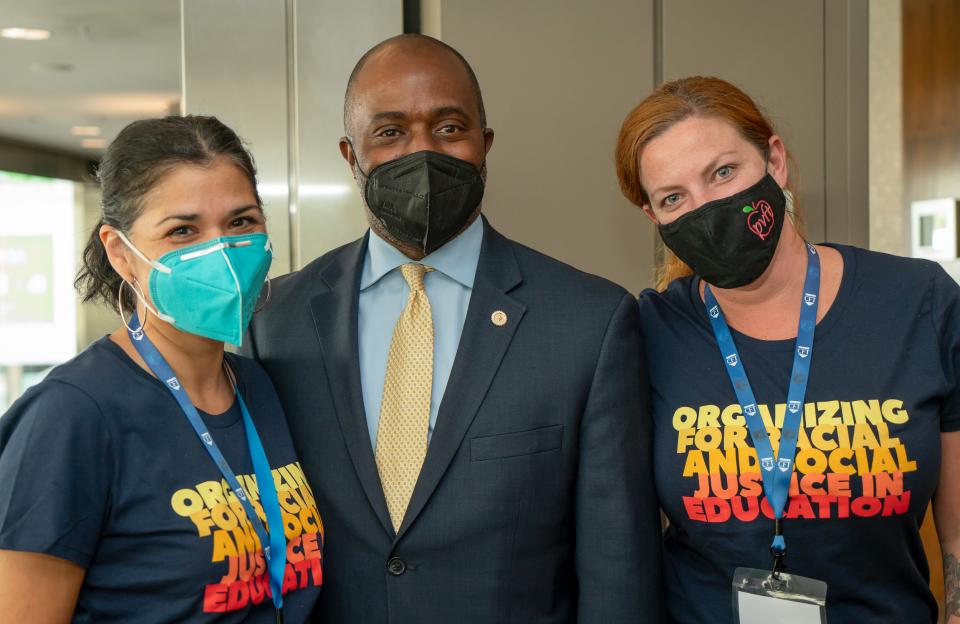

- Find resources for supporting undocumented students in our new toolkit: Organizing for Racial and Social Justice in Education.