Teacher, union activist, author, and former CFT President Miles Myers died December 15, 2015, from complications related to heart disease. Over six decades, Miles devoted his career to improving educational standards and the conditions for teaching and learning in public education.

Miles was born in 1931 in Newton, Kansas. His family moved to southern California, and he graduated from Pomona High in 1949.

After graduating high school, he drove across the country with a

friend to Washington DC, where he met his then Senator, Richard

Nixon. While serving in the U.S. Army in Germany during the

Korean War, he traveled throughout Europe and beyond. He later

kept his enthusiasm for travel, taking his family—wife Celeste,

and three children—to Lake Tahoe, Hawaii, the Virgin Islands and

Europe.

After earning a bachelor’s degree at the University of California, Berkeley Miles taught high school English for seventeen years in the Oakland public schools beginning in 1957. While teaching he earned two masters degrees and a PhD in Rhetoric and Composition and Writing Studies at UCB.

Simultaneously with his teaching and advanced studies Miles became active in the Oakland Federation of Teachers, AFT Local 771, and in the statewide CFT. Soon after Raoul Teilhet was elected president of the CFT in 1967, Miles was appointed editor of California Teacher, a position he held from 1970 until 1985.

Active in the union

The California Federation of Teachers was the pioneer voice

calling for a law enabling collective bargaining in California

public education, sponsoring the first bill in the state

legislature in 1953. Miles had been elected a CFT vice president

when he served as the organization’s legislative director in

1971, advocating tirelessly for a bargaining law in Sacramento.

That same year the California Teachers Association dropped its

longstanding opposition to collective bargaining. Miles educated

many legislators about the need, but he was a few years ahead of

the game. When the Educational Employment Relations Act finally

passed in 1975 and took effect in 1976, Miles and other CFT

leaders and staff took proud ownership of the

law.

Reflecting years later in the labor history documentary video series Golden Lands, Working Hands on the long struggle for collective bargaining, Myers commented, “From the beginning, we did not say to ourselves, “We’re going to get power by going to Sacramento and getting a bill that tells us that we have the right to collective bargaining.” We wanted that, but that was not the source of our authority. The source of our authority was in collective action, and watching the peace movement, and the civil rights movement, we could see the strategies one used.” [See short clip with Miles]

Miles was elected CFT president in 1985, succeeding Teilhet, and served until 1990. In these years he advocated for education not only through the mechanisms of unionism, but as a writer, thinker and organizer for new ways of understanding literacy and for the classroom authority of teachers. He proposed that the people who knew best how to improve classroom practices were not academics, politicians or businessmen, but teachers themselves.

Teachers as researchers into their own classrooms

Miles told us that the way to accomplish this was for teachers to

become researchers into their own classrooms. Their research

would provide the evidence for changes that needed to be made to

achieve more effective teaching and learning. He advanced these

ideas through books on writing and literacy, including The

Teacher Researcher: How to Study Writing in the Classroom (1985)

and Changing Our Minds: Negotiating English and Literacy

(1996).

For Miles, the goals of the CFT and what he was proposing for teachers as classroom experts were, at one level, the same thing. They were both about teacher power. Where they differed was that while the union helped to achieve that power through collective bargaining, the way other workers did, classroom research, properly performed and applied, would allow teachers to achieve power by taking control of what people called—but was actually not yet—a profession. He believed that establishing teaching as a profession requiring two things that teachers didn’t have enough of: expertise and school site authority.

He warned against two typical mistakes: seeing teachers as already professional, just because someone called them that; or seeing teachers simply as workers, whether through the lens of an administrator who was happy to keep them that way as their boss, or through the perspective of a type of unionism stuck in an industrial model. He thought that that model was a necessary step, laying down a base line respect, but on the way to something different: a union that facilitated a transition from teaching as an occupation to teaching as a profession.

Like Raoul Teilhet, Myers also saw unionism as a vehicle for broader social justice goals. During his presidency CFT opposed United States intervention in Central America on behalf of right wing regimes facing people’s insurgencies, and supported the struggle against apartheid in South Africa.

Inexhaustible energy

With seemingly inexhaustible energy, Miles, in 1974, co-founded the Bay Area Writing Project (BAWP) at UC Berkeley, which became the basis for a national literacy-based curriculum model, rooted in the belief that teachers are the best teachers of teachers. He was deeply committed to the organizations inspired by BAWP, including the California Writing Project and National Writing Project.

In 1990 Miles left CFT to take a position as the Executive Director of the National Council of Teachers of English at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, for seven years. Most recently he was chairman of the Curriculum Study Commission of Northern California and worked as a consultant with the Institute for Research on Teaching and Learning. He was often called on to testify before legislative bodies and state educational agencies in hearings related to teaching, standards, assessments and literacy.

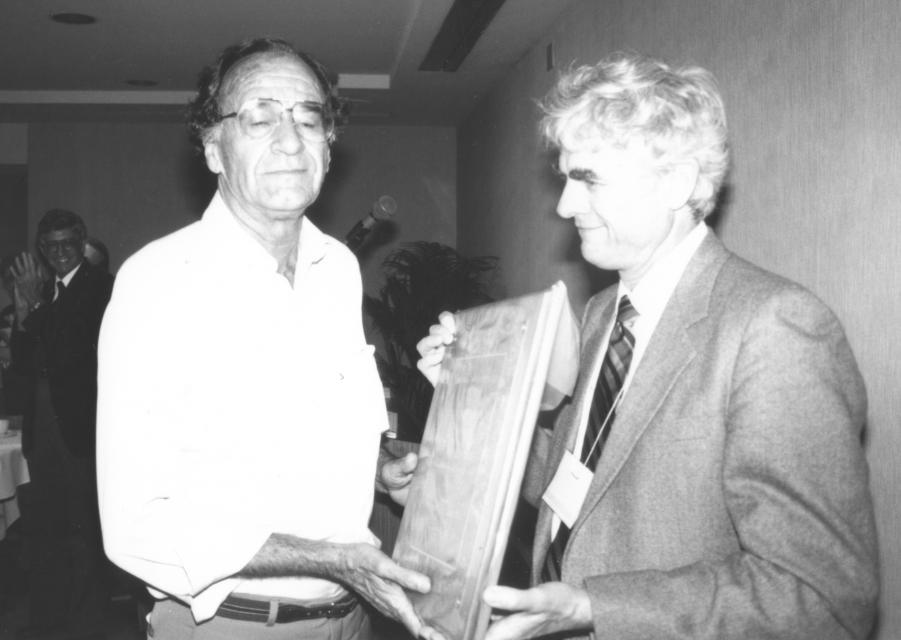

Miles received the CFT’s highest honor, the Ben Rust Award, in 1994. In 2014 he helped to lead the memorial celebration of the life of his friend and colleague, Raoul Teilhet, at the annual CFT convention.

Miles is survived by his wife of 59 years, Celeste, his three children Royce, Brant and Roz, three sisters Jean McClard, Joan Hope (Cecil) and Patty Gatlin (Dennis), six grandchildren and one great-grandchild. He is preceded in death by his sister, Roxye Jelden. He was 84.

The thing Miles loved most was browsing for books at a bookstore or the library. According to his wife Celeste, he purchased tens of thousands of books, and kept every single one. The family asks you to honor Miles by buying a book, reading it, and then donating it to a library.

Related article: Raoul Teilhet, 1933-2013