By Bill Morgan

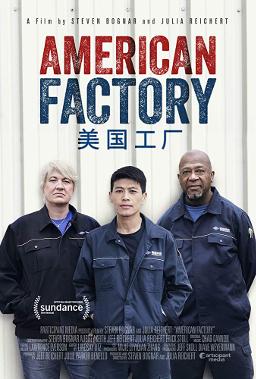

- American Factory (2019, Netflix)

- Directed by Steve Bognar and Julia Reichert

I know, you’ve seen them before: hard-hitting documentaries about workplaces, filled with candid interviews and tough, unstinting footage of workers organizing and management tactics to forestall them. The problem is, the unions usually lose these days, one way or another. We are left with those fleeting moments of courage and solidarity as our only inspiration.

American Factory belongs to this genre but adds to the mix the complication of different cultures – Chinese and American – and their approach to work. Scenes shot in a Chinese factory show workers lining up each morning, counting off in order, responding loyally and loudly to their group leader’s admonitions to work as fast and as hard and as much as they can. A similar scene in the company’s Dayton, Ohio, factory falls flat on its face.

From the very beginning, the bosses’ worst fear is that a union will come in. What are the managers and the CEO so afraid of? Easy. They are afraid the union will lessen their more or less absolute control over the work and the people who do it.

Candor there is, as managers walk the factory floor together pointing out workers they are about to fire for being pro-union or for working too slowly; workers talking about making half what they used to make and trying to live on it; a worker who has signed on for two-year hitch crying over his separation from his family; arguments on the floor; loud and raucous union meetings as the UAW takes up the campaign.

The clear theme of the film is the work-world view of the two cultures: the Chinese, with what might be called Communal Capitalism, dedicated to the company and its profits, loyal to the managers. (Of course, it all stops being “communal” when the profits are distributed.) The Asian workers miss their kids and families in China like everybody else, but the company is more important. Their success is the company’s success. If they are to succeed as individuals it will be incrementally within the company or not at all.

Jump to the American workers, individuals struggling along, trying to raise kids, thankful of course for the work, but watchful of their dignity, and suspicious of their managers, Chinese and otherwise. Many are looking at ways to make their work better and to achieve more control over their work. They are well aware of their situation in the scheme of things. They no longer have illusions about the goodness of their bosses or much enthusiasm for the company’s shapeups and slogans.

They need what the Chinese system has imposed on workers: a sense of community, a sense of a higher purpose. This is what carries the Asian workers through. They have this community though they have no control over their work. Theirs is a society of conformity and complacency, and if they have to leave their homes and families for two years, they will do it, to please the bosses and demonstrate their loyalty. A “lucky to have a job” sort of thing. Security comes from the company.

The film is very good though, beyond all these things that I mention. It demonstrates two versions of work that stretch before us. Shall we be extensions of the factory, working as fast as we can so the boss – regardless of ethnicity – makes more money, inspiring ourselves and one another to greater effort, or will we maintain some of our humanity and struggle for more control of the places where we work and the conditions under which we work? These are the stark choices the film presents.

Tantalizing questions, of course, remain. What percentage, for example, of the Asian workers at Dayton voted for a union? How many Americans voted against it? Why? What price profit?

The film’s coda throws out another consideration that is over the horizon and already reaching into our workplaces all over the world — automation. By 2030, 375 million people will need new automation-proof jobs. That is true for all of us, Asian and American — a basis for cross-cultural organizing, to be sure.

Somos todos trabajadores. Let’s find our common

interests and fight for the future together.

— Bill Morgan is member of the Labor and Climate Justice Education Committee and a retired elementary teacher from United Educators of San Francisco, AFT Local 61