Power Despite Precarity: Strategies for the Contingent

Faculty Movement in Higher Education

By Joe Berry and Helena Worthen

Pluto Press, 2021

Reviewed by Geoff Johnson

If there were two words which often define what may best be termed the “contingent condition,” they would be alienation and powerlessness.

Too often contingent faculty feel disconnected from institutions that do not pay them equally in regard to their full-time and tenured counterparts, and this is exacerbated by lack of health benefits, job security, support, and inclusion. Further, sometimes when adjuncts turn to their unions for relief, they may find their concerns classed as “unwinnable causes.”

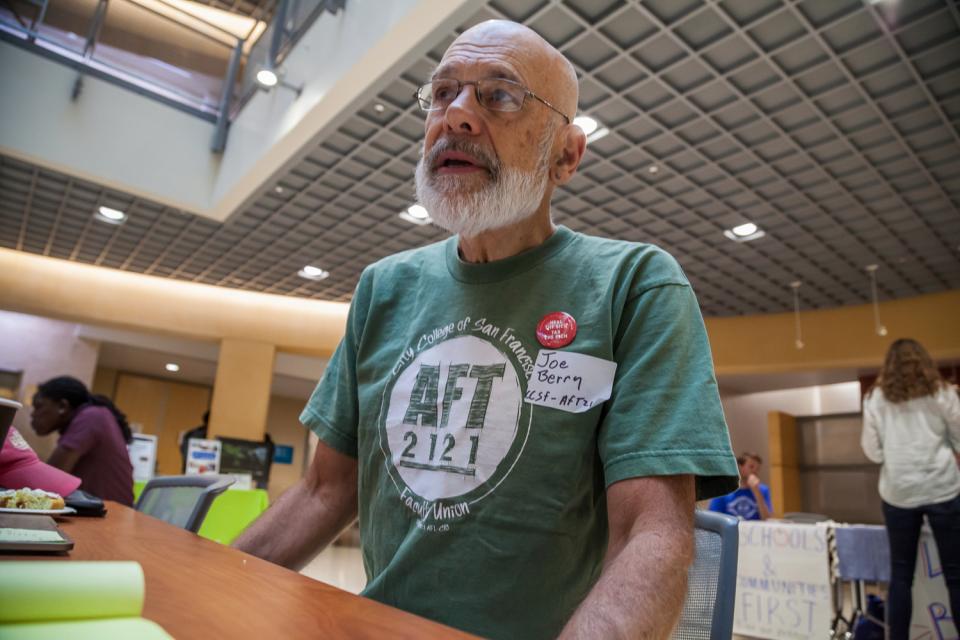

Long-time activists Joe Berry and Helena Worthen show how it doesn’t have to be that way in their latest book, Power Despite Precarity: Strategies for the Contingent Faculty Movement in Higher Education. Berry is a member of the Retiree Chapter of the San Francisco Community College Federation, AFT Local 2121-R, and a regular participant at CFT events. Worthen was the first editor of the CFT newsletter Part-Timer when it launched in 1990, and Berry was in charge of distribution.

Berry and Worthen are contingent faculty activists whose direct experience with contingent faculty working conditions and labor organizing dates to the early 1980s. They draw upon their long arc of experience and deep knowledge on the subject, including the observations of their comrade in arms, the late union activist and organizer, John Hess, to give the history of how CSU lecturers were able to build power within the California Faculty Association which was initially cool if not hostile to their concerns. In so doing, the contingent faculty created solidarity and collective power culminating in threats of strikes in 2007, 2011, and 2016, leading to what Berry and Worthen argue “is generally thought of as the best contract for contingent higher ed faculty in the United States.”

Along the way the book discusses the larger history of the “casualization,” or “adjunctification” of non-tenure-track faculty in relation to an increasingly corporatized and diminished higher education system, provides a deeper explanation of academic faculty unions, their processes and challenges, and explains how contingent faculty can organize and work to build power through their unions.

For those part-time faculty who are aware of the inequity in the United States and, particularly the California higher education system, the book provides a solid picture of how contingent faculty became marginalized by government and administrative policy. The subsequent results were terrible and even regressive contracts for contingent faculty.

What turns the tide, as Berry and Worthen show partly through the observations of Hess, is a combination of what they refer to as an “inside-outside strategy”, meaning that while contingent faculty must work within the union power and leadership structure, they must also organize their fellow contingent workers outside that structure to listen to and acknowledge contingent concerns, build solidarity, and in turn either shape or take charge of leadership to get their demands met at the bargaining table.

The authors essentially define a “blue sky,” situation, pointing out both what is possible and should be fought for and negotiated in a union contract beyond just pay increases, such as salary schedules with equal steps for advancement, access to health benefits, job security, academic freedom, and intellectual property rights. While great progress has been made, Berry and Worthen acknowledge more is to be done, but are relatively optimistic.

What’s particularly notable here is that while Berry and Worthen do recognize divisions and tensions between contingent and tenure-track faculty, they primarily argue that it is by forming solidarity between the two groups that greater success is attained. This is not to say that part-time only faculty units should necessarily form joint, or wall-to-wall units with full-time, tenure-track faculty, but that they should seek to create dialog and form understandings with them for greater solidarity and success.

Further, and where the book really shines, is in its latter sections, where Berry and Worthen talk about the nuts and bolts of organizing, from dealing with challenging and often fully unanswerable questions like whether organizing around hope or fear is more effective in a situation, or how to deal with contrasting ideologies between new and old guard activists, to identifying enemies and allies (such as students). Included with this is a clear discussion of labor law followed by coming contingent and higher ed concerns which every adjunct organizer or union rep would do well to read. Here is where the book evolves from being merely informative to actionable.

In no knock on either author, there were times when I wanted to

see more of the conversations at the CFA bargaining table, and

the before and after specifics of successive contracts, which are

alluded to but never fully written out. In fairness though, the

authors invite the reader to go look at the latest contract,

which is readily

available online, as if to tell the would-be contingent

activists reading this to begin the hard work of fighting for

equity on our own.

Geoff Johnson is a part-time English instructor and member of the AFT Guild, San Diego and Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community Colleges, serves as assigning editor of Part-Timer, and is a member of the CFT Part-Time Faculty Committee.