Raoul Teilhet, a Pasadena high school history teacher who believed collective bargaining offered the path to dignity and respect for public school employees before laws existed allowing it, and served as president of the California Federation of Teachers in successful pursuit of that goal, died of complications from Parkinson’s Disease on June 5, 2013, in Los Angeles. He was 79.

When Teilhet began teaching in the late 1950s, he “didn’t have the least intention of organizing a union, or becoming a member of one.” He would later joke that he “thought that AFT was the other end of a boat.” But when a national AFT organizer called a meeting in 1960 in a nearby town, Teihet was one of a handful of teachers who signed the charter founding the Pasadena Federation of Teachers, and he agreed to serve as its first treasurer. Within a few years he was elected local president, then a member of the statewide CFT Executive Council, and CFT president in 1967. Teilhet spoke out against the Vietnam War and the anti-gay Briggs Initiative when few labor leaders were ready to do so. Under his leadership the CFT grew from six thousand members to nearly 40,000 by the time he stepped down in 1985. And his forceful advocacy was one of the main reasons why the California state legislature passed, and Gov. Jerry Brown signed, the Educational Employment Relations Act in 1975, legalizing collective bargaining in California public education.

Raoul Edward Teilhet was born in Pasadena December 13, 1933. His mother’s people were from rural Arkansas, and his father, a baker, came to southern California from a coal mining family in West Virginia and Ohio, the only one of his brothers who didn’t work in the mines. Neither parent made it past sixth grade. Teilhet’s father died when Raoul was eight. His mother, whose politics Teilhet later characterized as “pure Roosevelt Democrat,” remarried during World War II.

At the time the Pasadena school district included a junior college, and by Teilhet’s own account his initial experience with higher education was a disaster. So he welcomed the day “when Harry Truman sent me a letter offering me an alternative lifestyle” during the Korean War.

When he returned from his military service he was ready to go to Cal State Los Angeles on the GI Bill, where he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in history. He was pleasantly surprised to hear he could earn $5500 a year to talk about history in front of high school students. He applied, and was hired, at his old high school.

At the time, new teachers had to join the local, state, and national affiliates of the then anti-union National Education Association as a condition of employment. Its state affiliate, CTA, was a professional association that provided a package of insurance programs for teachers, and lobbied in Sacramento. But it was firmly opposed to collective bargaining, and allowed administrators to participate in and often lead the organization. Teilhet had held union cards in the Teamsters, Laborers and Machinists unions when working summers and at night during college, so he was surprised to find his principal signing him up into the teacher’s association. Teilhet concluded that if your boss is signing you up, this must be a company union.

Teilhet felt no fear of overbearing school administrators, even in an era with the lingering hangover of McCarthyism evident in conservative pressures on curriculum and witch hunts of local teachers suspected of “Communism.” At a meeting in which the assistant superintendent of instruction put his arm around a teacher whom, he assured the crowd of teachers and parents, had been cleared of such charges, Teilhet wasn’t satisfied. He stood up and asked whether the administrator, if this should happen to Teilhet, would be out on the limb of academic and intellectual freedom, or standing there with the saw? The administrator looked at Teilhet and said, “What’s your name?” Teilhet stated his name, but as he pointed out in telling the story years later, hearing the name doesn’t do much good for knowing how to spell it. As the crowd was drifting out, Teilhet’s colleagues made cracks about his impending departure from the school district.

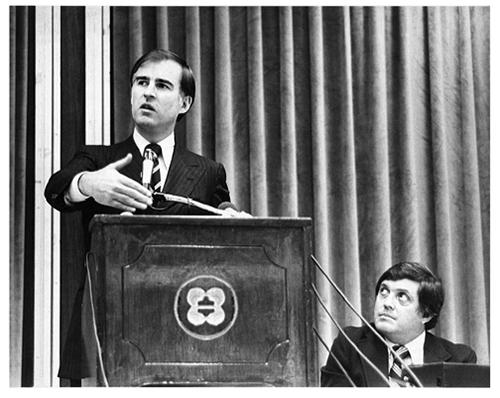

Teilhet speaking, AFT president Al Shanker listening.

He wasn’t fired—largely because the assistant superintendent in fact had no idea how to spell the name of this new teacher—but the next time Teilhet challenged school administration, none of his colleagues were laughing. He had been part of a committee vetting textbooks for a new curriculum on international ideologies to be folded into the high school social studies sequence. One book, an anti-communist rant, was written by a professor Teilhet characterized as “of dubious academic distinction,” and the teachers’ recommendation to the school board did not include that book. Whereupon the school board thanked the teachers for their work, and revealed it had ordered thousands of copies of the book the previous fall, and it would be the one used.

Teilhet quickly learned that the association he belonged to was not a vehicle for advancing his economic interests. Assigned to a toothless “salary committee,” Teilhet had thought teachers would come up with a wage proposal and strategize about how to get it. But sitting in the middle of the meeting was the district personnel director. Teilhet wondered how the teachers would come up with an effective strategy with a manager in the room. His wonderment turned to something else when he realized the manager was chairing the meeting. Teilhet asked him wasn’t there a possibility that if they came up with a strategy for their salary demands, the personnel director might not be able to withstand pressure to reveal it to his superior administrators? The personnel director’s response was first to inform Teilhet that teachers don’t “demand” anything, because that would be “unprofessional.” Then he suggested Teilhet might find another committee to serve on.

Instead Teilhet found a group of likeminded teachers, like himself mostly young, mostly Korean War veterans. Their experience in the military had left them unafraid of conflict and with “a great distaste for unrestricted authority.” Through their shared experiences with poor administrative judgment and decisions that ran counter to their ideas about schools and democracy, they arrived together at the fateful meeting with the AFT organizer and the understanding that they would found a union.

Similar experiences were piling up in school districts across California, as Teilhet quickly discovered. The success of the AFL-CIO—then at the height of its influence and power—in bringing a middle class standard of living to private sector workers and their families, did not go unnoticed by public employees. And the first teacher collective bargaining agreements in eastern urban centers in the early sixties helped fuel the belief of California teachers that their ideas weren’t completely utopian.

No one had more to do with spreading the word than Teilhet. When he was elected president at the 1967 CFT convention, the delegates made the position full-time for the first time. This upset some of the union’s traditionalists, who feared rank and file control of the organization would be lost; but the union’s growth demanded the change. Teilhet and his small but fervent staff crisscrossed the state setting up scores of new AFT locals in K-12 and community college districts, and in the university systems.

Known for his sharp wit and an endless supply of well-turned phrases, Teilhet was a masterful public speaker and charismatic organizer, inspiring a loyal following for the CFT mission of a collective bargaining law. He was immensely popular with the rank and file because he spoke their language, knew their grievances, and could articulate a broad social justice agenda that placed teachers at the center but also emphasized the connections that radiated out from education to the rest of society. He based that vision in the idea that the CFT should stake out more progressive positions than the CTA on every issue possible.

Thus CFT came out early against the Vietnam War. CFT members demonstrated and walked picket lines alongside Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers on behalf of farm worker rights, and Chavez and hundreds of UFW members came out to the CFT-led March for Education in 1967 in Sacramento. Teilhet saw affirmative action as a logical extension of the civil rights movement, and pushed the national AFT to develop a standing committee addressing women’s issues. Later, when reactionary state senator John Briggs attempted to pass a statewide initiative banning gay teachers from the classroom, Teilhet debated Briggs across the state, in front of campus audiences and cameras, and played a major role in the ballot measure’s defeat, at a time when anti-gay prejudice kept many other union leaders from joining the fight.

As the teacher union movement grew, Teilhet’s rising stature was reflected in his inclusion on the California Labor Federation’s Executive Council. As a vice-president of the state AFL-CIO, Teilhet solidified the relationship of workers without collective bargaining rights to those who had enjoyed those rights since passage of the National Labor Relations Act. And he built sympathy for the educators’ quest for bargaining rights among even the more conservative trades, which prior to the late 1960s hadn’t always believed public employees should have those rights.

In 1971 Teilhet and the CFT opposed the Stull Bill, a piece of legislation authored by San Diego County Assemblyman John Stull requiring teachers to be held accountable through a behavioral goals and objectives approach to teaching. A mountain of paperwork accompanied the new evaluation approach, which CFT believed would result in “assembly line classrooms.” Teilhet debated Stull on live television, while a phone-in vote from the public was tallied on screen, showing public opinion in favor of the CFT president’s positions. CFT made 16mm film copies of the debate and circulated it throughout the state in organizing meetings. The film was the first look for many teachers at Teilhet in action, and its wide dissemination was largely credited with CFT’s gain of five thousand members in less than a year.

By the early 1970s the swift growth of the CFT provoked major changes in the much larger CTA. In 1971 it embraced collective bargaining and removed administrators from its membership. With the teachers’ organizations united on the issue, a collective bargaining bill carried by Senator George Moscone passed both legislative houses in 1973. But then governor Ronald Reagan vetoed it.

Two years later Jerry Brown put his signature to SB 160, the Educational Employment Relations Act. Authored by State Senator Al Rodda, a former AFT local president, the bill empowered certificated and classified school employees in K-12 and community college districts to bargain collectively with their employers, and set up a state board to enforce the law. Teilhet and CFT celebrated, but their enthusiasm was tempered by the bill’s failure to include curriculum within the scope of bargaining, and by the exclusion of the CSU and UC systems. Following through on a promise to Teilhet, however, Brown signed a bargaining bill for higher education two years later.

Despite his stature and accomplishments in California, Teilhet was never elected to the national AFT executive council. As the leader of one of the largest AFT state affiliates, this would have been a normal course of events. However, the CFT’s opposition to the Vietnam War, and Teilhet’s outspoken advocacy on the issue, kept the state and national organizations at odds. It also didn’t help Teilhet’s cause that he had chaired the campaign for reelection of AFT national President Dave Selden in 1974, when Al Shanker unseated him to become AFT president.

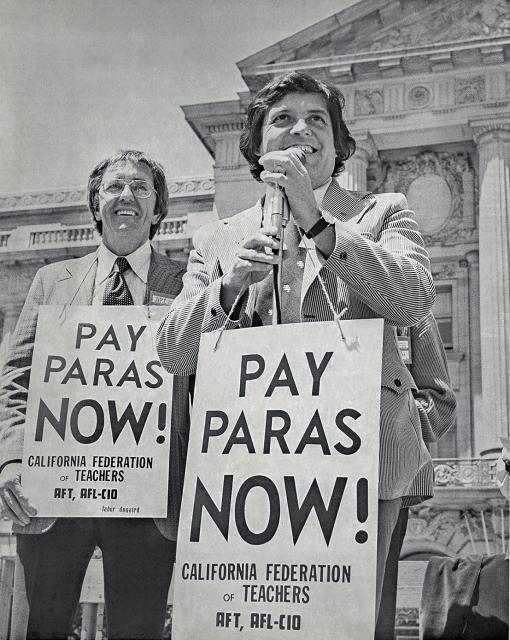

Teilhet welcomed the participation of classified employees in CFT, beginning with San Francisco paraprofessionals but soon extending to all types of school employees. Without downplaying the tensions and conflicts that sometimes arose between the two groups, he viewed their membership alongside teachers as providing for greater strength in collective bargaining for everyone.

A socialist in the Michael Harrington mold, Teilhet belonged to the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee, the labor-oriented faction that emerged from the old Socialist Party when it split in three. In 1980, on the eve of the Reagan era, he signed up with Harrington and a few dozen others in a Socialist caucus of delegates to the national Democratic Party convention. As with his early opposition to the Vietnam War and forthright defense of gay teachers, Teilhet’s socialist politics put him at some public risk. But Raoul Teilhet never shrank from fights over the principles he believed in.

Teilhet stepped down from CFT’s top leadership position in 1985, when he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Slowed but still effective, Teilhet’s services were retained by CFT for several more years as administrative director.

Raoul Teilhet is survived by his wife, Carol Rosenzweig Teilhet.

Oral history of CFT and AFT by Raoul Teilhet

In 1986 the AFT recorded a three-hour oral history with Raoul Teilhet. It is a superb summary of the history of education unionism from the late 50s to the mid 80s, filtered through the sharp insights of the former CFT president. Find four parts here.