Tenuous system torn apart by denial of three-year contracts to experienced teachers

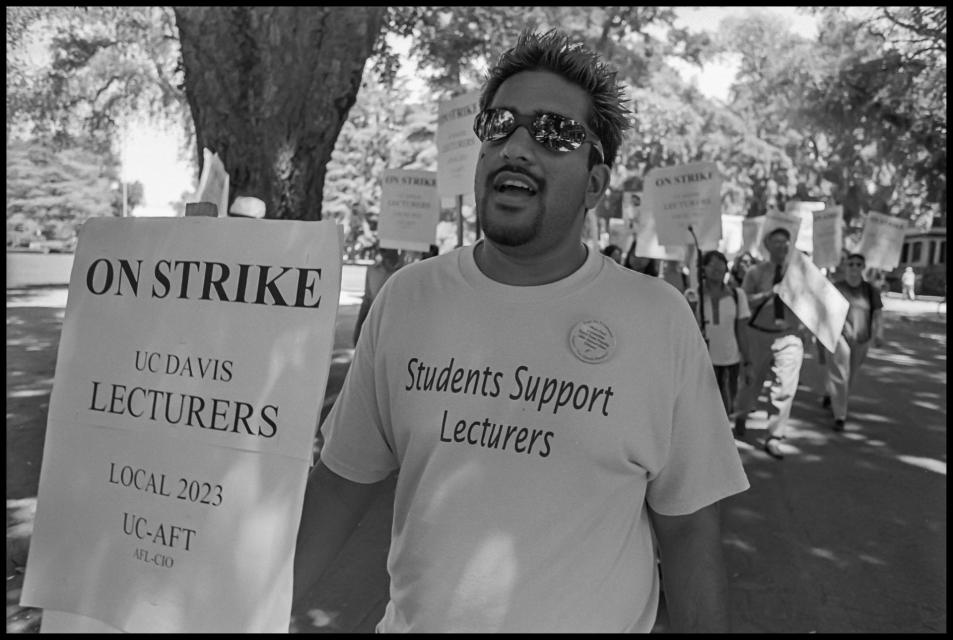

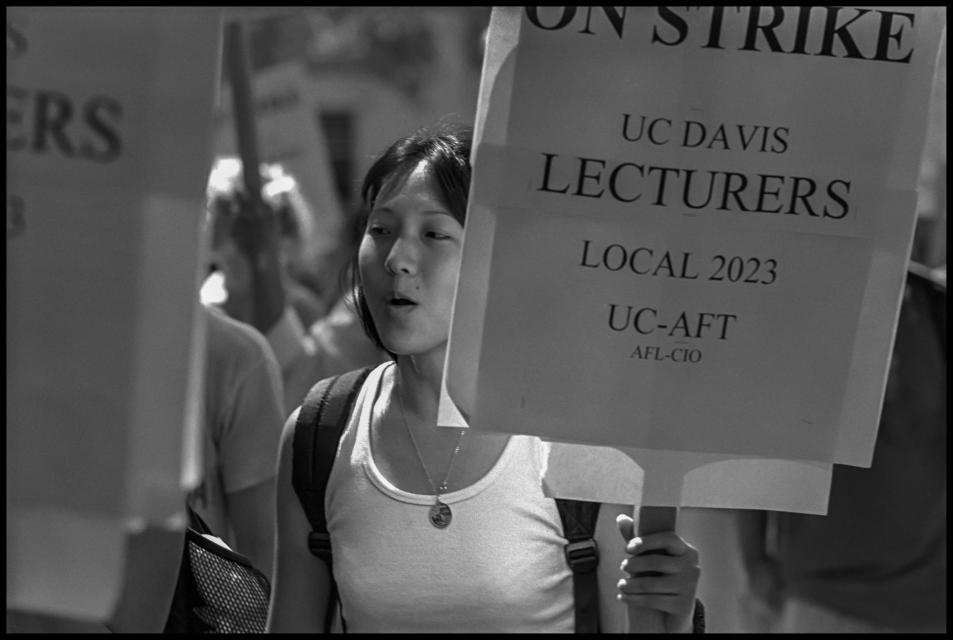

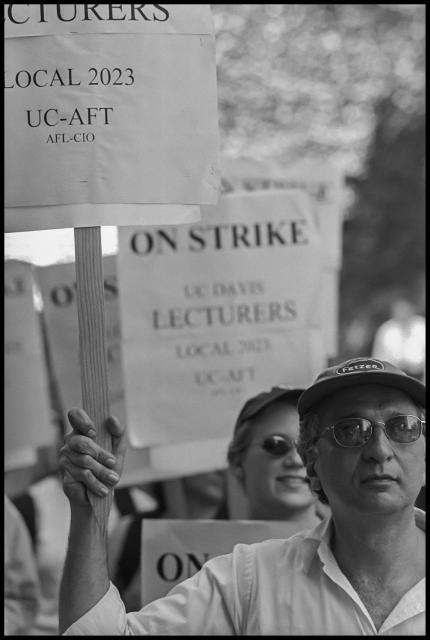

Anger among lecturers at UC Davis finally boiled over at the end of the spring semester. On May 29 and 30, 2002, non-tenured faculty walked the picket line instead of teaching classes, and turned the campus entrance on A Street into an impromptu educational institution.

From early morning to the end of the academic day, dozens of students, campus workers and tenured faculty gathered to talk with a committed core of instructors about a UC policy which makes job experience an unwanted qualification, and job security virtually unattainable.

Throughout the UC system, lecturers are initially hired on a year-to-year basis. That status, under present rules, lasts for six years. At the end of that period, all lecturers go through a grueling examination of the quality of their teaching, called the “eye of the needle.” If they pass through, they then win three-year contracts, which are normally renewed so long as they do their jobs well.

For many lecturers, even when the system functions as designed, it makes a normal life impossible. Among a group of five Spanish instructors at the A Street gate, four had yet to reach the six-year line. “We wait all summer to find out if we’re going to teach in the fall, and meanwhile, we better not get sick because we have no benefits,” charged three-year veteran Gabriela Avila. Maria Kilpatrick, with five years teaching Spanish, asked “How can we even buy a house if we don’t know whether we’ll be working or not?”

Three-year contracts denied

But in reality, the system at Davis doesn’t work as it’s supposed to since Dean Elizabeth Langland changed the rules. Problems started when she began giving reduced contracts to people who got their three-year contracts. Teaching loads (and therefore salaries) were reduced for some to 50 percent, and even as low as 17 percent of their previous levels. Many felt that the intention was to force lecturers to leave, just as they were supposed to have won a more permanent position.

Then this year a storm of controversy arose when she didn’t begin the process for granting three-year contracts to a number of lecturers in the English Department’s writing program, as they completed their sixth year. One of them, Victor Squitieri, had even been awarded the Excellence in Teaching Award in 2000, in a ceremony the dean refused to attend.

Another instructor, Amy Clark, was a finalist for the same award, and was also refused a three-year contract. Faculty and students in the department began to accuse the dean of undermining one of Davis’ strongest and most-needed programs.

Spanish lecturer Norma Lopez Burton explained that she supported the strike because, although she feels her own department supports its lecturers, “what’s happening in English could happen to us. The problem is general, and we’re showing solidarity to those that need it.”

Additionally, studies indicate that university enrollment is going to jump in the next few years, notes lecturer Michelle Squitieri. But instead of meeting growing need by keeping experienced teachers, the administration seems intent on replacing them with newly hired, and therefore less expensive, instructors on year-to-year contracts.

“We want the university to acknowledge that they can’t use this sixth-year process to eliminate long-term teachers for essentially economic reasons,” declared Squitieri.

Wide-ranging support for lecturers

The impact isn’t lost on Davis students, who turned out in great numbers for each day’s noontime march and rally. Jessica Clark, a fourth-year medieval studies student, called the lecturers who taught many of her classes the best teachers she had. “They’re the main reason that I stayed there — their dedication to students.”

Atul Nair, in his fourth year in economics, warned that UC policies endangered his education, since they were forcing experienced instructors to leave. “The dean can hire as many tenured faculty as she wants, but they shouldn’t replace the lecturers.”

Under pressure, Dean Langland has claimed she intends to rely more heavily on graduate student employees and tenured faculty to pick up the load. That scenario seems very unlikely, however. Michelle Squitieri notes that graduate student instructors cannot teach upper division courses, while tenured faculty can be expected to resist an increase in their class load as well.

Langland’s policy was also rejected by tenured faculty themselves. A town hall meeting of the Academic Senate, held the week before the strike, publicly repudiated her actions, and called for the writing program to be removed from the English Department and the dean’s responsibility, calling them unworthy stewards.

In fact, the Joint Audit Committee of the state Legislature is already investigating the university’s practice of basing requests for appropriations on assurances that highly paid professors are teaching classes which are actually taught by low-paid lecturers.

And Davis isn’t the only campus on which these changes are taking place, Other cases have surfaced at UC Riverside, while at UC Santa Barbara four lecturers received appointments, but at 11 percent of their previous loads.

“I think the strike really brought attention to something the administration wanted to do in secret, “Victor Squitieri concluded, “and the student support for it shows they’re seeing through this too. If the administration pushes through this policy, it will degrade their education, and it endangers it not just in Davis, but throughout the UC system”

Fight over job security as old as union itself

The fight over job security for lecturers is as old as the union itself. In 1983 more than 2,000 non-tenured faculty at eight campuses of the University of California voted for the AFT.

At the time, the issue was simple — the university’s hated “eight-year rule.” This regulation actually mandated that after eight years teaching for substandard salaries, the university would refuse to allow these teachers to continue in their jobs.

After winning the union representational election, UC-AFT negotiated a first contract, which eliminated the mandatory layoff, but still fell short of real job security. Union members have grappled with those shortcomings ever since, and they have resolved to make real progress in winning greater job security in the current round of negotiations.

Bargaining with the university has remained stalled, however, for two years. The union has proposed that lecturers be given a pre-review at three years, to let them know how it looks for a later appointment. Then, after the sixth-year ordeal, lecturers would be given three-year appointments that would be described as “continuing.”

University negotiators, however, seem to be moving backwards. They’ve proposed language that would allow the termination of a lecturer on a three-year contract for a host of reasons, including an administration decision to drop a class being taught, or simply a desire to save money.

One consequence of the protracted bargaining is that UC has withheld all cost-of-living raises from lecturers even though the funds for them have been appropriated by the Legislature. The administration is looking for a trade-off, in which lecturers would be forced to accept a substandard contract in order to get badly-needed raises in California’s high cost economy.

— By David Bacon, CFT Reporter