1970s: The Politics of Diversity

The struggle for collective bargaining took place against a backdrop of enormous teacher militancy; indeed, passage of the law finally came about after so many years precisely because of the pressure exerted on legislators by continuous teacher activism. As if eager to validate Teilhet’s assessment of how to win members away from the CTA, delegates passed a series of radical resolutions at the CFT convention in December 1969: against the Viet Nam war; calling for abolition of the draft; setting up draft counseling centers in junior high, high schools, and colleges (and supporting the rights of teachers to hold open discussions on these issues in their classrooms); for affirmative action hiring in public education; for birth control, abortion rights, maternity leave and adequate day care facilities; and supporting a plethora of student, minority, women’s and labor struggles. The CFT’s budget passed a quarter million dollars, giving the organization an unprecedented ability to turn its ideas into action.

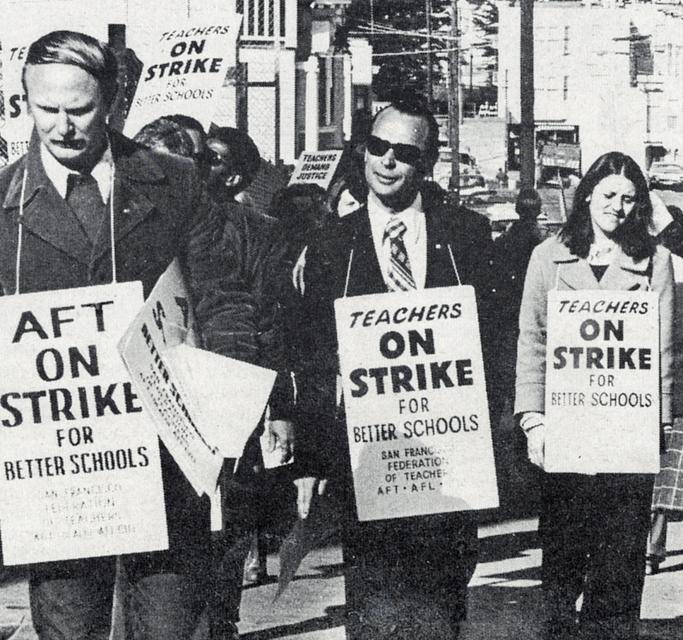

Not content to leave its positions on paper, the CFT continued to fight and win court battles, to push for legislation around teacher rights, and increasingly, to strike to back up local demands with teacher power. The union led a second march of several thousand in Sacramento against cuts in education in 1971. Annual CFT Civil Rights Conferences were held beginning the same year. Revealing substantial courage, first the San Francisco, and then the Los Angeles Archdiocese teachers organized themselves into AFT. Dozens of locals around the state picketed, massed their members at board meetings, and struck; the pages of California Teacher in the early 70s are covered with photos and stories about walkouts: in 1973-74 alone 42 locals engaged in some form of militant action.

Early in the decade New Leftists who had become teachers formed a loose statewide radical caucus, which produced an irregular newsletter (Network), criticized CFT policies deemed too mild and ran slates of candidates at CFT conventions against Teilhet’s Unity Slate. Its activists included Sheila Gold, Joel Jordan, Al and Kathi Rossi, Ed Walker, and Bill and Brenda Winston, among others. Several, running on militant (sometimes abrasive) platforms, were elected to local and statewide posts. While many of its members continued to be active, the caucus itself faded out of existence in a few years. Members of another radical grouping, the national AFT United Action caucus, were also active in California at the time. Independent candidates such as Berkeley teacher Dick Broadhead in 1972 ran and won CFT office (vice-president) against Teilhet’s slate.

In these same years, while the CFT continued to articulate the union’s traditional progressive agenda, the AFT national leadership grew more conservative. The change in the national union reflected the rapid shift in the late 60s to collective bargaining in many large cities. Locked in bitter conflict with the NEA for national leadership of rapidly unionizing teachers, AFT struggled with the tough issues of school funding in declining urban areas, and decreasing support for urban education.

The NEA sought to regain its lost national prestige by portraying the union as racist and authoritarian. Bolstering its own image, the NEA elected its first black president in1968, and invited a series of prominent black activists to specially advertised national conferences. Meanwhile, AFT leaders faced the job actually bargaining in urban schools, grappling with the issues of community control and decentralization. (The NEA was still officially opposed to collective bargaining.) In 1968 the national union endorsed decentralization but in Oceanhill-Brownsville, New York Local 2 president Albert Shanker took a stand against community control of schools. Other AFT locals in Detroit, Newark and Chicago did not agree with Shanker’s position on community control, but they endorsed the New York teachers’ right to strike and fight involuntary teacher transfers (the central issue of the Oceanhill-Brownsville conflict). The NEA was happy to exploit this division in its rival. By the time Shanker won the national AFT presidency in 1974 the Association was publicly calling itself a union.

A close look at NEA policy will reveal that in the fight against racism and for urban public education the NEA historically played a poor second fiddle to the AFT. In fact, the NEA did not completely integrate its chapters until 1974. The AFT willingly suffered the loss of thousands of members back in 1957 when it expelled its remaining segregated locals in the South. In later years, however, the national union has from time to time held positions disagreeable to the CFT, such as the AFT’s support of Allan Bakke’s “reverse discrimination” case. The CFT passed resolutions and demonstrated against the Bakke suit.

Because the AFT is a federation of locals the entire debate over community control in the union was held openly; the disagreements among unionists were often bitter and public. This is the messy strength of union democracy. The CFT and many of the California locals debated the issues as vigorously at the local level as they were debated nationally. California teachers maintained their progressive positions independently from the national organization, and at times have been able to influence the AFT by uniting with other like-minded teachers from around the country. An example of such influence was the galvanizing effect California women had on the AFT in the early 70s.

The 1972 CFT convention, addressed by then-AFT president Dave Selden and Democratic Party presidential candidate George McGovern, created a new entity, the CFT Women in Education Committee. Seats on the committee were hotly contested in this heyday of the Women’s Liberation movement. The CFT Executive Council appointed Wanda Faust of Poway as its first chairperson; under her leadership the committee (including Marge Stern, Julie Minard, Gretchen Mackler, and Pat Stanyo, among others) held the first CFT Women in Education Conference in the fall attended by over 150.

The Women’s Movement had a major impact on the AFT, reflected in the formation and activism in California of the Women in Education Committee. But the effects were national in scope. Marge Stern, a San Francisco teacher, was the first and most consistent voice for women’s issues in the national AFT. In 1970 she organized women (and men) teachers around the country and pressed the national union to create the AFT Women’s Rights Committee. Stern is known as the “founding mother” of the teachers union’s concern with women’s issues in both California and the nation.

With the Women in Education Committee as its conscience, the CFT moved its concerns over sexism into the legislative arena. The Committee, seeking to implement Title IX of the federal Civil Rights Act, called attention to sections of the Education Code relating to the portrayal of minorities in curriculum and instructional materials, and pushed the CFT to sponsor bills that added women to these Code sections. SB 450, for example, carried by George Moscone in 1973, mandated that all classes had to be offered equally to boys and girls. The CFT also drafted and secured passage in 1975 of a crucial bill carried by Howard Berman providing for maternity leave for teachers.

The Community College Council of the CFT gave organizational shape to the growing numbers of CFT faculty from the community colleges. Los Angeles Community College history teacher Hy Weintraub, president of the Council for much of the decade, worked closely with former AFT vice-president Eddie Irwin on the Council’s publication, The Perspective, to help bring a coherent statewide identity to community college faculty. Formed in 1971, the CCC devoted considerable energy to support the Peralta court case, which was filed in 1974 to fight for tenure for part-time Community College instructors and establish guidelines for their hiring and retention. Convention resolutions in favor of pro-rata pay and benefits for part-timers were backed up by actions such as the Peralta decision (finally achieved in 1979), demonstrating that CFT was the only organization that cared about these much-exploited teachers.

Community college faculty came to play a greater role in the CFT during the decade as their weight within the organization increased. By 1979, under Weintraub’s leadership, the CFT was growing faster than any other community college organization in California. Weintraub hoped that the CCC’s gains might encourage the Faculty Association of California Community Colleges (FACCC) to join the CFT. Unfortunately the CCC’s longstanding offer of unity was not accepted. That position put forward by the Council, however, demonstrated to community college faculty that the teachers union stood for a united teacher organization, and helped the CFT immensely during organizing drives.

Collective Bargaining

In preparation for collective bargaining the CFT helped fund local organizing efforts. In many cases these were tied to local attempts to subvert the weak “CECs” (Certificated Employee Councils) established by law in 1965. Some explanation of these “meet and defer” councils–as they were derisively known to union activists – is necessary.

In the aftermath of the New York AFT strikes, even CTA leaders recognized that it would only be a matter of time before public sector collective bargaining came to California. By 1965, in order to stave off the inevitable, the Association sponsored the Winton Act, which established “professional negotiations” for teachers. (Gordon Winton, defeated for reelection in 1965, was immediately hired by the California School Administrators Association, which at the time was part of the CTA.) The difference between the Winton Act and the earlier Brown Act was that Winton created “CECs” made up of 5, 7, or 9 teachers from employee organizations.

The only two representatives of education groups to speak against the bill at legislative hearings were the CFT’s Marshall Axelrod and Bill Plosser. The CFT opposed the Winton Act because it wasn’t collective bargaining, its meet and confer results were not binding on school boards, and because it called for allocation of seats on the councils based on membership, not through secret ballot elections. The CTA’s intent was to dominate the councils through their overwhelming numerical superiority.

The effects of the CECs varied from district to district. In some places the councils met, delivered their recommendations to the school board, and things remained the same. In other districts some CEC resolutions were taken seriously. For the CFT, CECs were inadequate in any case because they relied on the goodwill of administrators and school board members. Many CFT locals boycotted the CECs for the first several years, and in some districts the CTA chapters didn’t even bother to implement their own law. By the early 70s, however, CFT local leaders, instead of simply scorning the councils as a poor substitute for collective bargaining, began to use the CECs to achieve recognition by their school boards as legitimate teacher representatives. They had found that elections to the CECs could be used as an organizing tool; teachers were asked to join the AFT in order to increase the union’s representation on the councils. These were the efforts aided by CFT financial and organizing assistance. Meanwhile the CFT and its locals continued to struggle to change the Winton Act, and to push for true collective bargaining. In San Francisco union teachers achieved a breakthrough. In 1969 the school board allowed a secret ballot election to determine teacher representation. San Francisco Federation of Teachers Local 61 won. SFFT president Jim Ballard analyzed the results of the vote against the numerically superior SFCTA. He concluded that the ballot proved the Winton Act wrong to assume that membership numbers translated directly into the will of the teachers.

Each legislative session the CFT introduced a new collective bargaining bill, working closely with other public sector unions to create bargaining for all public employees. Collective bargaining was getting closer: in 1971 the union achieved the first full legislative hearing on the topic. Pressure was now beginning to build for collective bargaining within the CTA, too. Dissatisfied Association members were leaving and joining the union. In 1966 the CFT had 70 locals; by the end of the decade, more than 100. In 1976, the year that the Rodda Act became law providing for teacher collective bargaining in California, the CFT boasted nearly 150 active locals. The CTA officially joined the collective bargaining crusade midway through the 1971 legislative session to support CFT bills carried by Assemblyman Ken Meade and Senator Mervyn Dymally. It reacted just in time to prevent the CFT from overtaking and sweeping it aside in what was becoming floodtide for teacher unionism.

The CTA also suffered from their support in 1971 of the Stull Act. Passed over the fierce opposition of the CFT, the Stull Act demanded that teachers be held accountable through a behavioral goals and objectives approach to teaching. The law sought to turn the classroom into assembly lines, with measurable “productivity”. A mountain of paperwork was combined with the threat of negative evaluations for student results over which the teacher had no control. The law also undercut due process rights by eliminating the recommendation from hearing officers to school boards on sufficient cause for dismissal. California teachers were furious.

Raoul Teilhet appeared on a southern California television program to debate John Stull, and cut the hapless Republican Assemblyman from San Diego County to ribbons. A phone-in vote from the public tallied while the program was on the air showed public opinion in favor of the CFT president’s positions. (What actually happened was this: the broadcast was taking place in conservative San Diego County, and the vote probably would have gone against the teachers except that a CFT flyer had warned locals in advance to get their members to ring the phones off the hook at the program.) The CFT made a 15mm film of the program, and circulated copies of the film to teachers’ lounges all across the state, publicizing the union’s opposition to the bill and the CTA’s support of it. The union picked up 5,000 members in less than a year.

The California Labor Federation and the CFT asked Senator George Moscone to carry a collective bargaining bill for teachers in 1973. With the support of United Teachers of Los Angeles and the CTA, he introduced SB 400, which called for repeal of the Winton Act and the creation of comprehensive collective bargaining to replace it. After passing the state senate and assembly, it was vetoed by Governor Reagan in September. A moral victory, this was the first time that a teachers’ bargaining bill had made it as far as the Governor’s desk. It took the election of Jerry Brown as Governor, committed to collective bargaining for teachers, to tip the balance of forces.

The next year, seeing the writing on the wall, the California School Boards Association proposed what in their view were acceptable parameters for collective bargaining. Teilhet penned a California Teacher editorial in April, 1974 responding to the CSBA entitled “All of the Associations Now Support Some Collective Bargaining for Teachers -What Do We Watch Out for Now?”

“We union teachers did not join the AFT and work for collective bargaining just to get a higher salary, a bigger insurance policy, a longer leave and shorter hours. We wanted some of those things, but we also wanted to secure smaller classes, adequate supplies, better books – a more humane and creative environment for learning. To leave curriculum in the hands of the Board would be to abandon one of AFT’s most essential goals. This issue makes imminently [sic] clear that the Board has moved to the point of accepting teachers as employees who have something important to say about how much they earn, but not to the point of accepting teachers as policy makers in schools.”

Teilhet had scanned the future accurately. In 1975 Senator Al Rodda, a former AFT local president, introduced SB 160. Trailing behind a comprehensive bargaining bill for all public employees that didn’t pass the legislature, SB 150, for K-12 and community college teachers only, moved through both houses and was signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown.

The Rodda Act was not a perfect law. For one thing, the CFT didn’t like the narrow scope it imposed on what could be bargained. The Winton Act had had extremely broad scope but no mechanism to enforce agreements. The Rodda Act provided the enforcement mechanism but restricted the scope of bargaining to wages and benefits, hours, and working conditions.

Worse, it left the universities out in the cold, a fact decidedly unappealing to the several thousand member strong UPC (United Professors of California), the State university section of the CFT. After an emergency State Council meeting in August, 1975, the CFT reluctantly supported the bill, since it did not appear likely that anything better could be passed. Despite its shortcomings, passage of the Rodda Act represented a signal victory for the organization that had, on principle, introduced teacher collective bargaining bills into legislative sessions time and time again since 1953.

At mid-decade in the 1970s the AFT was the fastest-growing union in the country. In California the numbers kept pace as the CFT approached 30,000 members. Unfortunately the state union wasn’t quite big enough to take full advantage of the Rodda Act. The CTA still had more than five times as many members. Thousands of CTA teachers were undoubtedly sympathetic to the union, but stayed with the Association for its insurance and financial programs.

For practical and ideological reasons the AFT, under the leadership of David Selden (AFT president 1968-74) proposed merger to the NEA and held discussions in the early 70s, at national, state and local levels. A united organization would have meant an immeasurable gain in strength for teachers everywhere; it would have become the largest union in America. The NEA had moved a long way towards becoming a union, accepting collective bargaining and strikes. National AFT-NEA talks collapsed in 1974, however, partly over the question of labor affiliation, one issue on which the NEA remained adamantly “professional.” ‘While local merger talks continued, few Association chapters were willing to buck their national organization’s position, although not for lack of local AFT offers. The CFT’s standing offer of unity to the CTA provided a vision of the promised land for California teachers throughout the decade, one which served the CFT well in its struggle for their hearts and minds.

At about the same time, back in the trenches (and almost by accident), the CFT nearly managed to affiliate an entire chunk of the CTA. In 1972 the CTA raised its dues to its several geographical sections around the state, causing a rebellion in southern California led by UTLA’s Executive Director Don Baer. CFT and UTLA leadership met with CTA chapters from San Diego to Santa Barbara. The rebel CTA chapters decided to call themselves UTAC (United Teachers Association of California), wrote up articles of confederation, and developed a timeline with arrangements to join CFT after two years of independent existence. By refusing to pay the new dues to CTA, UTLA brought NEA into the picture. The NEA spent a fortune setting up a new chapter in Los Angeles, CTA-LA; it never gained more than 800 members. The rebellion collapsed when the NEA, realizing the futility of its dual union strategy, offered in essence to pay off UTLA’s debt (about a million dollars). UTLA pulled out of UTAC, rejoined CTA, and the other chapters followed suit.

The California collective bargaining law took effect at the beginning of 1975. The first election for an exclusive representative bargaining agent was held in spring in the Tamalpais school district. The AFT won. In the next few years the union won dozens of local election victories, including San Francisco and several other large districts. But in many districts the AFT lost, including some of the Federation’s oldest and most active locals: Sacramento, Richmond, Oakland and San Diego. In some places the union reverted to its role as gadfly of the larger Association. In others, union activists gave up their charter, joined the local Association chapter and tried to transform it into a real union from within. In still other districts the AFT survived, thrived on Association mistakes and decertified the local chapter within a year or two.

But one result of the coming of collective bargaining was that in just over a year the CFT shrunk by nearly one third. Membership plunged in districts after AFT lost the elections; where some locals with 500 members existed in 1975, by 1980 there remained but a handful of scrapbooks. The CFT was ironically for a union that had struggled so long for the opportunity, a victim to its own premature success. Given its momentum, if another few years had passed before collective bargaining was legalized, the CFT might well have been in a better position to challenge the CTA for statewide dominance. The Association lost more members than the CFT did, but they had more to start with; the statewide numbers game was essentially over by the close of the 70s.

Still, the CFT’s achievement was impressive. With less than one fifth the membership of the CTA when collective bargaining became legal, the Federation’s locals garnered almost 45% of the total votes cast statewide for the two organizations. In many districts the AFT lost by an eyelash. The moral victory – and pressure placed on the CTA to function like a real union – was considerable. As jurisdictional lines fell into place for teacher representation, the CFT began the hard work of helping locals to negotiate and enforce contracts. The union held training workshops for local activists and officers, and hired more statewide field representatives to service locals. Practically all of these were CFT teacher-activists, in keeping with the union’s grassroots philosophy. For example, the Community College Council had hired San Mateo Community College Federation president Pat Manning a few years earlier to lead school budget analysis workshops and organize. The CFT hired local activists Chuck Caniff, Mary Bergan, Clarence Boukas and Larry Bordan from its own ranks in the early 70s; in 1978 Marian Hull, Tom Martin and Julie Minard were added to the staff.

The union also started to consider other organizing opportunities. In 1972 paraprofessionals in the San Francisco Unified School District had approached the union regarding affiliation. In 1977 they became the first non-teacher bargaining unit within the CFT after the national AFT ruled that educational workers other than teachers could be admitted. That same year the NEA voted not to admit paraprofessionals as full voting members, while maintaining those rights for principals. (The NEA reversed that decision two years later.) Over the next several years many more classified units elected the AFT their bargaining agent.

A larger issue than how to negotiate and whom to organize soon overtook the union, teachers, public employees and the general public. In January 1978 California Teacher warned CFT’s membership about Proposition 13, the property-tax cutting initiative placed on the ballot by right wing populists Howard Jarvis and Paul Gann: “If passed, it would decimate the current system for raising money for public schools and other city/county services that are substantially dependent for a significant amount of their revenue on the property tax.” SB 90, in 1972, had already limited school revenues based on property taxes; so schools hadn’t gained anyway from the higher property tax revenues received by the state from 1972-78. The union joined in a coalition with the California Labor Federation, the CTA and a myriad of other organizations to oppose the initiative. Throughout the year the CFT’s presses worked overtime to educate teachers about the devastating effects on education and other social services that would be caused by prop 13. The CFT contributed money – the locals raised over $135,000 – and grassroots teacher power to defeat the initiative, to no avail.

Passage of Proposition 13 meant that public sector collective bargaining in California faced extraordinary problems just as it was getting off the ground. In addition to severely curtailing government services and laying off thousands of public employees, Prop 13 managed to change the rules of the new arrangement in a fundamental way. The union’s assumption had been that local school boards would continue to exercise the ability to generate local revenue through taxes. Proposition 13 shifted nearly the entire school funding mechanism to the state. This shift undercut collective bargaining’s promise of shared governance through co-determination of the allocation of resources by board and union. School district money was now fixed by the state, leaving little room for local flexibility at the money end of bargaining.

Prop 13 gave school boards a chance to plead poverty and uncertainty even if their coffers were full. Since Prop 13 and collective bargaining arrived simultaneously, it confused many teachers, causing some of them to blame their deteriorating conditions on collective bargaining, not Prop 13. And the more cynical school board members and administrators adroitly fanned that flame.

In one narrow respect the whole tax-revolt nightmare may have been a blessing in disguise for fledgling union negotiators; it set them down in a political pressure cooker, out of which they emerged as far more sophisticated bargainers than they might otherwise have become so quickly.

The new situation tightened the bonds between the CFT and its locals. For the first several decades of its existence the CFT had lived by the simple maxim that the statewide union was only as strong as its locals. In the 60s, with the explosive growth in membership and consequent strengthening of the CFT, locals grudgingly recognized the necessary coordinating role of the CFT. After Prop 13, teachers were much more directly dependent on Sacramento for their salaries, and had to rely on statewide political action to a far greater degree than before.

In the midst of the turmoil generated by Proposition 13 two important events occurred which also pointed toward the next decade. In April 1978 the Pajaro Valley Federation of Teachers in Watsonville “dis-elected” the Association chapter, winning the opening round in a struggle that continues to this day between CFT and CTA. This was the first decertification of a previously elected bargaining agent in California. (If only unity talks had prevailed!) By the end of the decade the CFT had won several more decertification elections, and bargained for school employees in over 50 districts.

In September 1978 Governor Brown, making good on a promise to the CFT, signed AB 1091, which authorized employees of the state university and UC systems to engage in collective bargaining. UPC, which represented a plurality among state university faculty, and which had been (in different organizational forms) for nearly twenty years a vocal and active section of the CFT, began to prepare for the coming struggle. In fall of 1979 on the first day after the new law went into effect, UPC filed a petition for representation signed by over 50 % of the unit. The election, however, would not be held until1982.

The final year of the decade was pockmarked by the predicted effects of Prop 13. All across the state school districts were laying off employees, teachers and classified, occasionally even administrators. One of the hardest-hit cities was San Francisco, which laid off a staggering 1,200 staff. In response the SFFT, teachers and paraprofessionals, went out on a strike that lasted six weeks and resulted in the rehiring of over 700 of the laid-off employees. But it was a pyrrhic victory. Two years later, strike weary teachers decertified Local 61 as bargaining agent. While maintaining a large and active membership, the local remained in non-bargaining agent status for the next 8 years. The local – and the CFT – learned an important lesson about the negative consequences of overly-aggressive leadership and too many strikes bunched together in too few years.

Meanwhile, just 15 miles south of San Francisco, AFT Local 1481, representing the Jefferson Union High School District teachers and classified, hit the bricks and stayed out for 44 days, protesting teacher layoffs and contract take-backs in the longest and most bitter school strike in the state’s history. In the middle of the strike the local CTA chapter, adding insult to injury, reversed an unspoken agreement between NEA and AFT to respect each other’s picket lines, crossed the lines, and filed a decertification petition. Despite the betrayal, the union won back all the jobs and successfully defended the contract. The CTA chapter withdrew its petition.

As the 70s ended the landscape of teacher unionism in California had been irrevocably transformed. The CFT, after hitting a high of 30,000 members and plunging down to 20,000, steadily recovered, gaining back half of the loss during the ‘election years’ of the last third of the decade. The union had maintained its political philosophy to the left of the association and used that position as a magnet to break away the CTA’s progressives. The CFT’s political course, as demonstrated in such action as staunch defense of minorities (against the Briggs anti-gay initiative and the “reverse-discrimination” Bakke suit) and helping teachers in trouble, coupled with solid footing on collective bargaining, helped hold the bulk of the membership of the union on board as political waters grew rough. CFT membership was for many activists a home of sorts, where the ideals of the 1960s social movements still shone brightly even as the country began its descent into the 80s and the accompanying partial eclipse of political reason.