With a massive outpouring of community support, a new generation of teachers shut down the country’s second-largest school district in a fight for the future of public education. UTLA members launched their first strike in 30 years to deliver “the schools our kids deserve.”

A week later they were well on their way.

This was the third major strike for United Teachers Los Angeles, and UTLA’s 33,000 members hit a grand-slam homerun for a half million Los Angeles Unified students. In the process, they made teachers into heroes again and mobilized the public to save public education.

“This was the best lesson you ever taught in your lives,” UTLA President Alex Caputo-Pearl told a roaring crowd in Grand Park the day after Martin Luther King Day, as he announced a tentative agreement with Los Angeles Unified Superintendent Austin Beutner after six days of striking.

Teachers would not return to work, Caputo-Pearl added, until strikers had a chance to read and approve the tentative agreement. Members held meetings on campus and voted that afternoon. Chapter chairs sent the results digitally to UTLA. With 73 percent of members casting ballots the tally was 20,024 in favor – 81 percent – and 4,696 against.

In December, an estimated 50,000 teachers, parents, students and supporters marched from Grand Park to the nearby Broad Museum, a shiny bauble built by local billionaire and charter school proponent Eli Broad. They called on Superintendent Beutner to:

- fully fund Los Angeles schools

- reduce class sizes, which often spike above 40 students

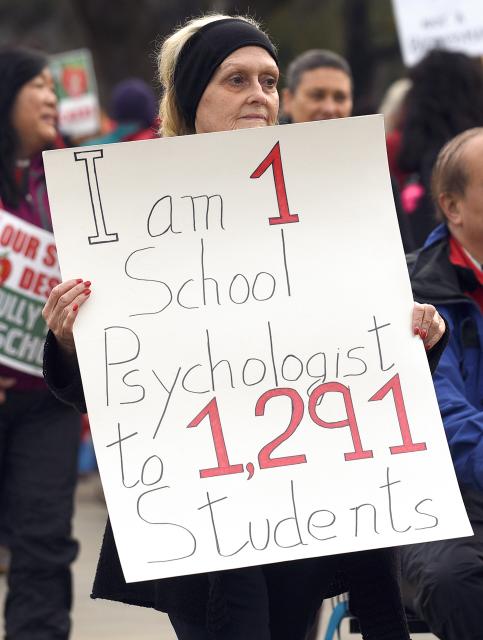

- hire more nurses, psychologists, counselors and librarians

- offer teachers a fair pay raise

- invest in community schools and stop the onslaught of charter schools

- reduce student testing and create a better learning environment

The successful strike brought historic progress in all those areas. The biggest problem at the bargaining table, however, was different world views. Or as the head of the UTLA negotiating team, Arlene Inouye, put it after nearly two years at the bargaining table, but before the breakthrough, “We haven’t had an honest partner.”

Beutner was a Wall Street wizard, but he has no education experience and many of his closest supporters see LAUSD as a failed social institution that should be replaced by charter schools.

LAUSD, on the other hand, like other California public schools, has been on the receiving end of decades of erosion in education funding as California, the fifth largest economy in the world, has fallen to 43rd of 50 states in per pupil spending. The unchecked growth of charter schools has only worsened other problems.

Caputo-Pearl later announced that UTLA members would stop teaching on January 10 unless negotiators could reach a fair agreement. Beutner responded much as he has during nearly two years of bargaining by claiming the district was about to go broke and trying to block the strike in court.

To avoid a legal challenge, UTLA delayed the deadline four days. When Monday, January 14 dawned, the response was phenomenal in spite of a massive winter rainstorm pummeling Los Angeles and the strikers.

Clusters of wet educators in red t-shirts with picket signs were seemingly everywhere, chanting “We are the teachers, the mighty, mighty teachers, fighting for justice…and for education.” For hours, they elicited passing drivers to honk their horns.

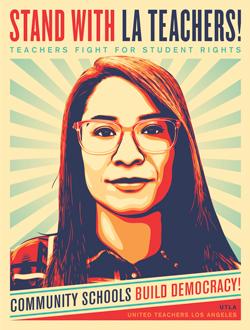

The new face for public education, Roosevelt High’s Roxana Dueñas, appeared on UTLA-sponsored billboards, advertisements and posters, and media outlets that had trashed Los Angeles Unified for years suddenly became the most ardent defenders of teachers.

Union supporters from fellow AFT local unions and firefighters to blue collar workers and movie stars pumped up picketlines and rallies. The labor movement was eager to take the offensive after years of attacks, including the Supreme Court’s recent Janus decision.

It was, indeed, the best lesson that Los Angeles Unified teachers have ever taught. The contract fight, however, was the first of three game-changing challenges.

Next up is a special election in March to replace a pro-charter school board member who was forced to step down. In a crowded field of 10 candidates, UTLA has endorsed Jackie Goldberg, long-time progressive, former teacher and state assemblymember, who began her political career on the school board. A May run-off is likely.

The third battle – passing the Schools and Communities First Act on the November 2020 ballot – will have even broader consequences. The CFT-backed proposition will restore more than $11 billion per year to the state’s schools and community colleges and other public services by closing a Proposition 13 loophole that allowed commercial property owners to dodge tax increases.

Last year, teachers struck for fully funded schools in Oklahoma, Arizona, Kentucky, West Virginia and Colorado, but activists like Inouye, also secretary of United Teacher Los Angeles, say UTLA’s militant stance stems more from close ties with the Chicago Teachers Union.

“Chicago changed the face of the union from being service-driven to being a powerful advocate for students and parent-community relations – the CTU strike in 2012 showed we can win,” said Inouye.

That was the year UTLA put forth a strong community-based vision of public education with the campaign “The Schools Our Kids Deserve.” Four years later, then-Treasurer Inouye led an internal union campaign called “Build the Future, Fund the Fight” that included raising union dues. An 82 percent majority of members cast “Yes” ballots in what she called “the most important vote in UTLA history.”

“The members believed in us,” Inouye said. “If we hadn’t passed that initiative, we couldn’t fight today for the schools our children deserve.”

UTLA has used that revenue to expand research operations, strengthen communications and organize a parent outreach program.

UTLA strikers weren’t alone on the picketlines

ON DAY ONE, nearly 400 members of SEIU Local 99 also walked out in solidarity at 10 Los Angeles schools. SEIU represents about 30,000 classified employees, including instructional aides, bus drivers, custodians and cafeteria workers.

Executive Director Max Arias said Local 99 “fully supports teachers in their demands for smaller class sizes, increased staffing, and greater investment in our children. The decision to strike is a difficult one, but ultimately it is a necessary step to make sure that frontline workers are heard.”

At the UCLA Community School in Koreatown, Frank Alas-Alegría and Yvette Monzón gathered strike pledges from 87 of the 91classified staff, including the cash-strapped spouse of a furloughed federal employee. About 70 percent of Local 99 members attended district schools, and nearly half are parents or guardians of school-aged children.

For her part, Monzón thanked LAUSD unions for their solidarity when Beutner dug in his heels during Local 99 contract negotiations last spring. “UTLA and the Teamsters said they wouldn’t cross our picket lines if we struck, and that forced administrators back to the bargaining table.”

Hundreds of additional Local 99 members launched solidarity strikes at 10 other schools on day five.

Social studies teacher Rebecca Solomon, the UTLA chapter chair at the Community School, said the classified staff “took a chance by going on strike, but joined without hesitation. They know that giving our students a good future is a shared fight.”

The classified staff took a chance by going on strike, but joined without hesitation. They know that giving our students a good future is a shared fight.

Confronting the charter school challenge

ON DAY TWO, tens of thousands of UTLA strikers converged outside the California Charter Schools Association office in Little Tokyo.

In 2005, there were 58 independent charter schools in the district. Today, there are 221, representing the highest concentration of charter schools of any district in the nation. One of every five LAUSD students now attends a charter school.

A 2016 fiscal analysis commissioned by UTLA found the district loses $591 million per year to charter schools. With “co-located” charters often sharing space with traditional district schools, the study revealed that LAUSD failed to collect millions of dollars from co-located charters for space they were given but didn’t use.

As money leaves the district, costs remain and even grow, including charter school oversight, infrastructure, and educating the highest-need students left behind by many charters.

“This is a fundamentally unsustainable path that threatens the very existence of the civic institution of public education,” the report concluded.

Earlier that day, about 80 UTLA members at three Accelerated Charter Schools in South Los Angeles launched their own strike after more than a year of fruitless contract talks. This is the first walkout at a California charter and only the second strike by charter teachers in the nation.

UTLA has organized three of the 25 schools in the Alliance for College-Ready Public Schools charter, where teachers signed their first contract in April.

Public opinion quickly becomes clear

ON DAY THREE, the Los Angeles Times front-page headline trumpeted “Teachers Bask in Public Support for Strike,” and a Loyola Marymount University poll showed that more than 82 percent of parents supported the teachers.

Count Jason McLaughlin as a supporter. McLaughlin stood alongside the Manual Arts High picketline, waving hello to strikers. The baseball scout grew up in the neighborhood and worked briefly at Manual Arts for a private company. His wife works for LAUSD and he stays in contact with many former co-workers.

“There’s nothing like a teacher,” McLaughlin said. “No computer can bring out the best in a child like they can. Why wouldn’t we want our children’s schools fully funded and their teachers paid fairly? We’re talking about our future.”

How popular are the teachers? At Robert Hill Lane Elementary in East Los Angeles, even sheriff’s deputies in patrol cars honk in solidarity when picket captain Loribeth Mau leads strikers in a spirited line-dance along Cesar Chavez Avenue.

Nineteen of the 20 teachers at Robert Hill Lane struck, but nearly twice as many people are picketing that morning. Supporters include spouses, children, neighbors and classified staff from East L.A. College across the street.

Morning rituals include giving the stink-eye to the lone scab as she crosses the line. On a sweeter note, toddlers wave to teachers from the school’s front door.

There’s nothing like a teacher. No computer can bring out the best in a child like they can. Why wouldn’t we want our children’s schools fully funded and their teachers paid fairly? We’re talking about our future.

Exhausted, wet and hopeful strikers

ON DAY FOUR, math teacher Julie Van Winkle and dozens of other strikers at the Sonia Sotomayor Learning Center in Glassell Park shout at cars trying to inch past them in a hard, driving rain.

“Between tinted windows and the rain, we can’t tell if the drivers are parents dropping children off, classified staff going to work, or scabs, so we yell at them all,” Van Winkle said, adding, “Respectfully, of course.”

Yaneth Flores teaches Spanish at Sotomayor. Flores kept her two children – a kindergartner and an eleventh grader – out of school this week.

“I’m exhausted but hopeful,” she said. “Every morning as I drive to the picketline, I think about how the changes we want will improve our schools.”

The salary increases the union seeks aren’t foremost on Flores’ mind. “Of course, I can use a raise, but 6 percent isn’t going to change my life. Smaller class sizes and more counselors will make my life – and all the kids’ lives – better.”

Van Winkle is a UTLA North Area Director and member of the union negotiating team. “We want to fundamentally change how this district spends money.”

Every year since she began teaching in 2004, Van Winkle said, the district has claimed that a financial crisis forced it to exceed caps on class sizes. “No other school district has an ‘escape clause’ like that in their contracts,” she said.

Of course, I can use a raise, but 6 percent isn’t going to change my life. Smaller class sizes and more counselors will make my life – and all the kids’ lives – better.

A break in the storm

ON DAY FIVE, UTLA and LAUSD negotiators returned to the table at noon and didn’t break until midnight. Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti hosted the talks at City Hall and dropped in periodically. The state’s new governor, Gavin Newsom, and new State Superintendent of Public Instruction, Tony Thurmond, were on call.

Tens of thousands of UTLA strikers, meanwhile, encamped across the street in Grand Park. Days of rain and rallies had turned the lawn to mud, giving musical performances by Tom Morello and Aloe Blacc and the many rousing political speeches a vibe somewhere between Woodstock and the Occupy movement.

Negotiators agreed to not speak publicly about the talks, but district leaders were striking a more conciliatory tone by early afternoon. School Board President Monica Garcia emailed thanks to all stakeholders, including striking teachers, nurses, counselors and librarians for helping “open so many people’s eyes to the underfunding of our public schools.”

— By Steve Weingarten, CFT Reporter