State Dept. of Public Health updates school reopening guidelines

CFT wants to see stronger guidelines

During his July 17 noon press conference, Governor Newsom announced statewide guidelines for reopening K-12 schools this fall.

While the governor addressed some of the demands that the union articulated to him and state leaders in the CFT letter sent on Monday, CFT still believes that there is more to be done to ensure the safety of California’s teachers, school staff, students, and communities.

CFT urges Governor Newsom to delay physically reopening schools

Surging coronavirus cases, testing woes make opening safely all but impossible

The CFT has asked Governor Newsom and state legislative leaders to delay the physical reopening of schools. Despite coronavirus cases surging throughout the state, growing numbers of hospitalizations and deaths, and mounting testing woes, some school districts are rushing to reopen — putting students, teachers, and communities at risk.

In a letter to state leaders, the CFT also urged the governor to provide stronger leadership and direction to school communities, who have been left on their own to make the difficult decision on whether it is safe to reopen schools.

Social worker’s outreach during pandemic leads to district-wide change

“We’re not just trying to teach — we’re in the in business of love and care…”

Leslie Hu, a social worker at San Francisco’s Martin Luther King Jr. Middle School, thinks that during a global pandemic, when many students are seeing their communities directly affected, isn’t the time for business as usual.

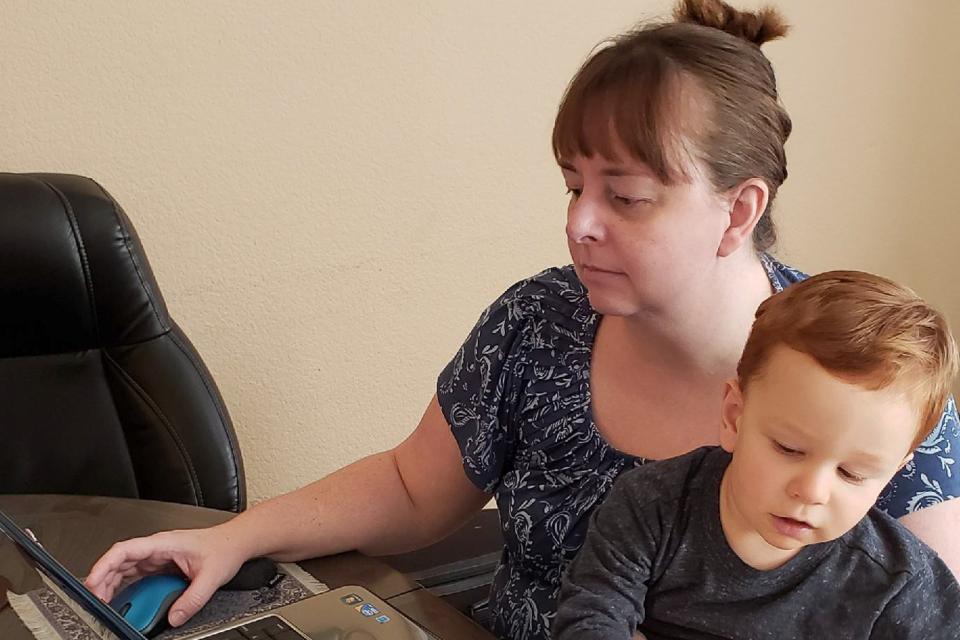

Tightrope Walkers: Teaching and parenting at the same time

Faculty parents share stories of teaching from home during shelter-in-place

By Katharine Harer, San Mateo Community College Federation of Teachers, AFT Local 1493

You’re teaching all your classes online, providing support to freaked-out students and dealing with a flood of emails every day, while at the same time, and often in the same room, hour after hour, your children need you to be present and available. You can’t send them to school or childcare or to the grandparents or to play at their friends’ houses. You can’t send them anywhere. Will lack of sleep, personal space and time make you trip and fall, and if so, who will catch you?

College students staying positive through the pandemic

Union presidents surveys students for newspaper column

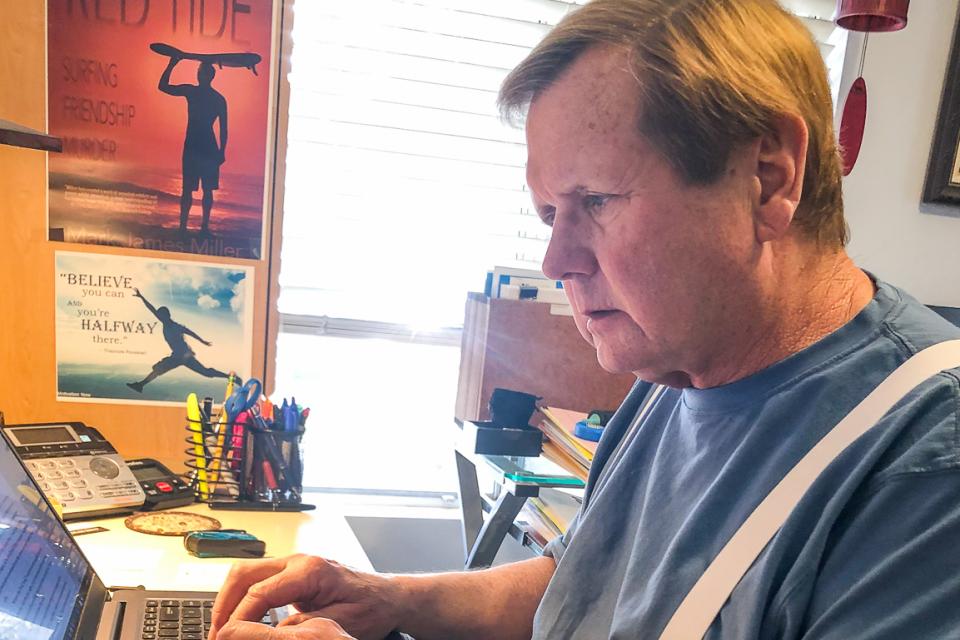

By Mark James Miller, Part-Time Faculty Association of Allan Hancock College

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought its own unique challenges to every facet of society. Everyone has been seriously impacted by the virus, and students in higher education are no exception.

Nationwide, students are delaying their education until the pandemic is over and colleges return to the traditional classroom approach instead of the online model being used in its place. Some are simply uncomfortable with online learning, and others are fearful that the education they receive remotely is not of the same quality as what they get in the classroom with the instructor present.

Dedication to students helps teachers make huge shift online with grace, diligence

Distance learning demands hard work, extra hours — and good internet

Since schools closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and instruction moved online, Jessica Hoffschneider, a resource special education teacher at Soquel High, has been busy. A site representative for the Greater Santa Cruz Federation of Teachers, she spends her days trying her best to help her students with mild to moderate disabilities.

Tech support powers online classrooms behind the scenes

Classified employees make the connections and keep them strong

Computer geeks have been on the front lines of online learning since March, when school and college districts across urban and rural California closed to avoid the COVID-19 pandemic. Tech staff are the essential employees who are turning digital classrooms from a pipedream into a working educational system.

College instructors rise to distance learning challenge

Extra hours, perseverance, union support assist in transition

Palomar College child development teacher Barbara Hammons definitely found the idea of distance teaching a challenge. For years, she and her department chair had a running joke – if she ever wanted to get rid of her, no need to fire her, just give her an online class.

Allan Hancock College teachers and the ‘new normal’

Union presidents surveys part-time faculty for newspaper column

By Mark James Miller, Part-Time Faculty Association of Allan Hancock College

“I miss the face-to-face contact.”

“Something is missing.”

“I miss being with my students.”

As Hancock College’s part-time instructors adapt to the “new normal” brought on by the coronavirus, one theme is constant: With all classes now being taught remotely, they miss being in the classroom with their students.

Adjunct faculty leaders organize, meet challenges of pandemic

The union picture — now and in the months ahead

The ongoing COVID-19 experience for part-time instructors has demonstrated their great collective strength and resiliency, despite limited pay, benefits, job security, and often minimal support.

Several local union leaders — who are part-time faculty — report that beyond the initially hectic and at times frenzied process of transitioning to remote instruction and services, faculty have more or less still been able to teach a semblance of their face-to-face course.

Part-time faculty face the travails of remote teaching

Stories of teaching from home during the pandemic

Within the span of just two weeks in early March, California Community Colleges, along with the rest of American higher education, were forced into the perhaps the largest and most radical pedagogical shift in its history.

The changeover at Allan Hancock College

Challenges and rewards of teaching online

By Mark James Miller

Even before Gov. Gavin Newsom’s shelter-at-home order, Allan Hancock College was gearing up to meet the challenges the COVID-19 virus presents to an institution of higher learning.

For faculty and students, this new normal brings with it many issues regarding how best to continue the mission of education — providing the students with the highest quality of instruction — while trying to remain free of the virus and maintain social distancing.

What does the overnight transition to “remote learning” mean?

For classroom faculty with traditionally scheduled on-campus classes

Note: This helpful article was written for a local community college audience, but many of the principles apply to all of higher education as well as K-12 education.

By Jim Mahler, President, AFT Guild, Local 1931, San Diego and Grossmont-Cuyamaca Community Colleges